IMF loans issued in the Americas and India to address foreign exchange crises ultimately weakened domestic economies and industries. China takes a different approach to lending by funding infrastructure abroad and securing resources to bolster its own economy. Countries that rely on IMF loans risk long-term economic setbacks, while China’s model strengthens its position as a global economic leader.

In the early 1980s, many Latin and South American countries, including those with big economies such as Mexico, Brazil and Argentina, suffered a debilitating foreign exchange crisis and were unable to service their foreign debt. These countries took foreign loans in the 1960s and 70s to develop and industrialize their economies. In the 70s, two sharp increases in oil prices worldwide caused a drain on the foreign exchange reserves of all oil-importing countries. This led the Latin and South American countries to default on their foreign exchange loans taken earlier.

As a result, the US stepped in to help these heavily indebted countries by rescheduling their debt payments and involving the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a global organization that provides policy guidance and financial assistance to member countries. The IMF gave the Latin and South American countries foreign exchange loans with the proviso of encouraging these countries to open themselves to foreign trade and allow freer imports.

While the IMF loans enabled these countries to tide over their foreign exchange crises and prevented a default on their foreign loans, they led to internal issues within these countries and sharp cuts in infrastructure, health and education outlays and layoffs of workers in many large public sector undertakings. The resulting high unemployment caused a rapid decline in living standards and negative economic growth, giving rise to the expression that these countries suffered a “lost decade.”

IMF borrowing in India

A similar situation occurred in India in the late 1980s. The Indian government pledged a substantial part of its gold reserves by physically transferring the gold overseas to avail of an IMF loan to weather its foreign exchange crisis. As in the past, the IMF imposed conditions to liberalize foreign trade so that the revenue from exports could service this loan. The import tariffs in India crashed from a high of 100% for industrial goods to a maximum rate of 7.5% or even lower by the end of by the end of the 1990s and into the early 2000s. At the same time, many Indian companies took foreign loans at much lower interest rates than those prevailing in India to save on their interest costs. The interest rates in India in the 1990s were around 18% to 20% compared to 6% to 8% internationally without hedging, but even after the foreign exchange risk was hedged, it was not more than 12%.

Initially, the Indian economy grew as a result of foreign investments into India both by Indian companies in their manufacturing activities as well as by the opening of the Indian financial markets to the world. This resulted in huge foreign exchange inflows from foreign institutional investors into the otherwise closed Indian stock market. At the same time, the clearing system of the stock market of manual accounting was computerized and standards were set, which led to the immediate settlement of the buying and selling of shares with strict safeguards and regulations. This brought about the explosion of the Sensex, a stock market index that lists India’s biggest companies, and India became the darling of overseas investors.

Simultaneously, remittances from Indians working in Middle Eastern countries contributed a massive influx of foreign exchange, which was actually the result of a lack of employment opportunities in India. All these measures led to greater foreign exchange inflows and imports of industrial goods into India, as they were cheaper than those made in India. In addition, a boom in software exports from India brought huge foreign exchange earnings. All this led to enormous foreign exchange reserves, allowing India to easily tide over the foreign exchange crisis.

The next decade beginning from 2000 saw Indian companies investing heavily in taking over companies internationally by pledging their Indian assets and also availing of foreign exchange loans. The Aditya Birla Group acquired Novelis, an aluminium manufacturing company in the US and Canada with global operations; the Tata Group acquired Jaguar, Land Rover and Corus Steel in the UK; and the Reliance Group invested heavily in the US fracking industry to produce crude petroleum. Large Indian business groups made many other acquisitions in Eastern European countries. With a healthy economic growth rate, India proved a success story to the world.

Problems emerge in India’s economy

In the decade beginning in 2010, the situation somewhat changed. India’s foreign exchange reserves remained healthy due to software exports, inward remittances from workers in the Middle East and foreign institutional investments in India. However, industrial activity declined sharply, leading both to the closure of many large sectors, such as calcium carbide in chemicals, and to the outsourcing of manufacturing overseas. Indian companies such as the Tata Group and Nirma Limited in the soda ash chemical sector acquired companies overseas and imported soda ash from those operations rather than expanding in India. Moreover, India’s imports of industrial goods increased drastically, and the current trade account shifted from a surplus to a large deficit of around $200 billion by 2020. While economic growth and the foreign exchange reserves remained healthy, the Indian industrial sector in manufacturing suffered a decline from over 33% in 2000 to a little over 10% by 2020.

The major reason for this was a lack of reforms within India for manufacturing and the economy internally. A sharp increase in indirect taxes, many of which could not be set off, further exacerbated this. This led to increases in the cost of production and the overpricing of inputs such as power, oil, transport and interest costs. For example, the transport costs from China to South India were only 60% of the transport costs between South India to North India due to over 100% taxation on gasoline and diesel.

India’s manufacturing collapse was matched by the boost in financial markets and software exports. However, high unemployment became a huge problem, as industry is a major provider of jobs. If India was not saved by its software exports and liberalized financial markets, it would have suffered the same fate as the Latin and South American countries, which it now faces about 30 years after the IMF loan taken in 1990.

IMF loans lead a country to import goods from the developed world rather than strengthen its domestic manufacturing base, resulting in greater unemployment and a lack of economic growth as exhibited by the Latin and South American countries. These countries use the foreign exchange loans given by the IMF for imports rather than building up the domestic economy of the country.

If the IMF loans were not availed of, in hindsight, it would have forced internal reforms and developed these Latin and South American countries instead of making them dependent on imports. It would have led to tremendous short-term pain for long-term gains by pushing governments to cut their expenses and become more proactive and productive.

China’s approach to lending

In contrast, Chinese lending to overseas countries differs greatly from that of the IMF. China was liberalized internally under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, its premier in the early 1980s. Its liberalization led to China becoming a powerhouse in manufacturing by the end of 2000 in a short span of 20 years. Its admittance into the World Trade Organization in 2001 with the support of the US made China a global player in the following years.

China became a manufacturing hub of the world with many developed countries of Europe and the US moving their manufacturing operations to it. These products were meant for consumption in the large Chinese market as well as for buyback by foreign companies for their markets. The huge arbitrage in costs led to all western countries’ sectors shifting their manufacturing operations to China. This boosted China’s foreign exchange reserves and export-driven economy to such an extent that China became the largest holder of US treasury bills. China has since then diversified its holding of foreign reserves into gold and other foreign currencies.

China gave a further boost to its local economy by developing the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2014, retracing the silk route from China to Europe and its string of pearls theory of developing strategic ports across Asia and the Middle East for facilitating foreign trade. The BRI’s costs were pegged at approximately $5 trillion, leading domestic Chinese steel and cement companies to export their surplus production for the construction of roads and ports internationally. Chinese banks financed the project with Chinese companies and workers involved in developing the infrastructure. This virtuous cycle exported Chinese economic growth across Asia and Europe.

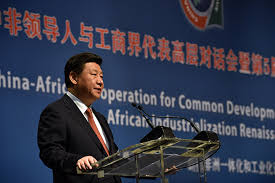

Similarly, Chinese companies entered Africa in a large way by roping in the heads of local African governments to their side, giving them incentives and developing their infrastructures. Again, the Chinese model of these projects was financed by Chinese banks with projects executed by Chinese companies with Chinese workers. China also extracted mineral wealth from these African countries for their domestic manufacturing industries in automobiles and electronics.

To further the string of pearls theory of international trade, the Chinese government developed the ports in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Djibouti amongst many others. This cut transport costs in moving goods between these countries into China. Therefore, these ports and the subsequent development of road infrastructure within these countries helped to deliver goods to China at much lower costs and made all the raw materials required for manufacturing goods available to China. China, in turn, used this infrastructure to export the finished goods.

The Chinese did not interfere in the domestic matters of African countries and institutions like the western world did to suit their purpose. Instead, the Chinese co-opted the local governments into their larger plan, leaving them free to rule without intervening in their affairs. Like any astute and careful lender, the Chinese secured their loans so that, in the event of any default, they could take ownership of these assets. Many countries such as Sri Lanka and Pakistan have become dependent on China due to their inability to service their loans. China receives flack from the western world for making one-sided contracts in their favor, but these complaints actually stem from unhappiness with Chinese dominance on the world stage.