[ad_1]

Speaking to Al-Arabiya TV last week, Kifle Horo admitted that both Egypt and Sudan might be affected by the filling of the dam. The third filling is expected to take place in August and September this year.

Despite such an admission of possible impact on downstream countries, Kifle added that the building of GERD would not stop for any reason because it does not involve Ethiopia and does not extend beyond the 2015 agreement on the filling.

“Perhaps it is surprising that the Ethiopian official did not care about the potential damage to the Sudanese side, despite his recognition of the possibility that both Sudan and Egypt would be affected by the third filling process, which indicates that Ethiopia wants to move forward with its previous unilateral positions,” the Sudanese foreign ministry said in a statement issued on 28 May.

On 20 February this year, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed inaugurated the dam as it officially began to generate electricity. At the time, he had said on Twitter: “This is good news for our continent and for the downstream countries we aspire to work with.”

2015 agreement

The agreement signed by Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan on 23 March 2015 in Khartoum lays out certain principles, such as that of cooperation. In particular is the “Principle Not to Cause Significant Harm”, that says: “The three countries shall take all appropriate measures to prevent the causing of significant harms in utilising the Blue/Main Nile.”

READ MORE GERD: The dam of discord

It further adds that should a “significant harm” come to one of the countries, the country who inflicted such harm, should “take all appropriate measures in consultations with the affected state to eliminate or mitigate such harm and, where appropriate, to discuss the question of compensation”.

Negotiations still at an impasse

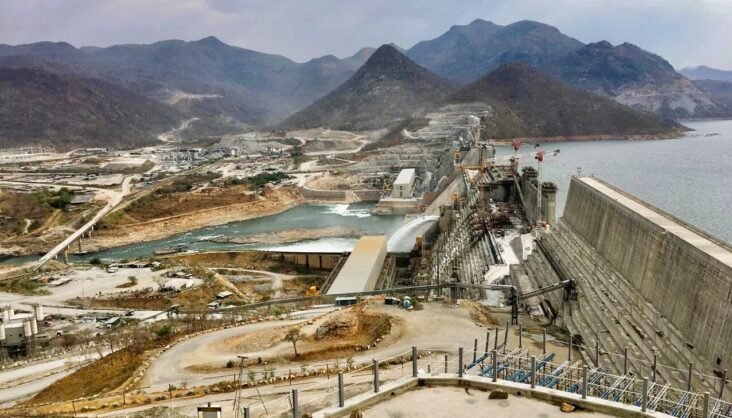

Since 2011, the GERD project, aimed to propel Ethiopia’s development through access to a constant source of electricity that it can also sell to neighbouring states, has always been called out for putting at risk countries downstream, namely Egypt and Sudan.

Upon completion, it will be Africa’s largest dam with a production capacity of 5000 MW – double Ethiopia’s current capacity.

Although Sudan was initially neutral to the project, in recent years, it has joined sides with Egypt in voicing its concerns about losing access to a vital source of water, the river Nile.

Both countries, along with international mediators (the UN, the US, the AU) and the regional bloc IGAD, have pushed for all sides to come to an agreement. Despite efforts by both Cairo and Khartoum for Addis Ababa to sign a binding agreement to the use of water, Ethiopia has begun filling the dam since 2020 at the peak moment of its rainy season between July and September.

The latest round of talks between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan in the DRC capital Kinshasa ended in early April 2021 with no progress made.

Historical claims

Downstream Cairo continues to revert to a treaty signed in 1929 under the colonial British ruling, that guaranteed it a “historical right” over the river; or in other words, Egypt has power to veto projects on the river.

In 1959, another agreement was reached between an independent Egypt and Sudan, in which Cairo was guaranteed a quota of 66% of the annual flow of the Nile, while Khartoum secured 22%.

Because Ethiopia was never a part of these agreements, it considers itself not bound to them and thus free to initiate its own projects found in its territory, regardless of the possible consequences downstream.

Added to that is the most recent treaty signed in 2010 by the countries of the Nile Basin, which originates in Uganda, that removed Egypt’s veto power to allow for irrigation and hydroelectric projects.

[ad_2]

Source link