This is part 4 of a 4-part series.

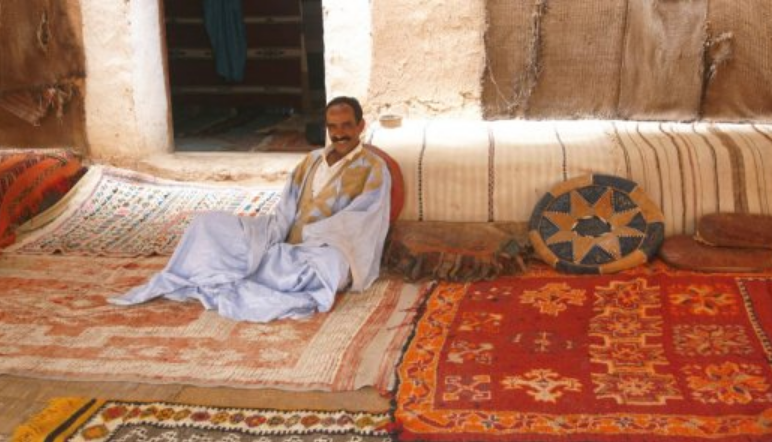

Alongside the very refined Beni Ouarain are shimmering red carpets that are historically associated with the Zayanes, a tribe located in the Middle Atlas. For a long time, these carpets were dyed using extracts of Rubia laevis and Rubia peregrina, two endemic varieties of madder grown in Morocco and the Saharan oases. Although the weavers have retained their know-how, the traditional dyeing process has gradually been abandoned in favour of faster and less expensive methods.

“Everyone is quick to claim the natural label on the pretext that three drops of henna have been added to the dye,” says Wilfrid Thoumazeau, co-founder of the carpet brand Secret Berbère, whose collection boasts some carpets made from vegetable dyes.

However, in Morocco, no one has worked with dye plants since the 20th century. Once the French arrived, the craftsmen switched to synthetic dyes.

Translation: A new carpet from Secret Berbère! Secret Berbère’s ‘Les Naturels’ collection… We use the best wool, the best hands and 100% vegetable-based colours.

Just like indigo, which is used in the textile industry, madder – as it is commonly known – is often mixed with environmentally harmful products. Recipes using heavy metals, which emerged before the advent of mass production, have been developed to ensure that the pigments last.

The article continues below

Free download

Get your free PDF: Top 200 banks 2019

The race to transform

Complete the form and download, for free, the highlights from The Africa Report’s Exclusive Ranking of Africa’s top 200 banks from last year. Get your free PDF by completing the following form

“Traditionally, the prettiest reds were made with tin salts,” says Patrick Brenac, founder of Green’ing, a company specialising in natural dyes that helped develop Secret Berbère’s ‘Les Naturels’ collection. However, Brenac remains honest about the process: “We colour our creations using small touches, because the technique of vegetable dyeing is very complex and involves several times of rise per vat of colour and cooling times. The collection required four years of research.”

Translation: Extracting colour from plants or insects is a difficult task. And yet it is the method that we at Secret Berbère use to obtain the colour of these carpets. The result is breathtaking and magical, we don’t do it for the clicks, but rather the nuance, the beauty, the softness.

So many components – including tin, but also lead and mercury salt – are now banned for ecological reasons. “We can no longer afford such processes,” says Brenac. “So we are gradually returning to the traditional methods, to natural chemistry.” However, it is difficult to find a perfectly green-friendly solution that will ensure that the colours dyed on knotted and woven wool last 100 years.

An “eco-friendly” Moroccan tradition

For example, mordanting (the process of preparing fibres to accept colour) still includes alum salt – an aluminium derivative found in cosmetics such as deodorant – which has been singled out by environmentalists.

According to Michel Garcia, author of the study Teinture Végétale Traditionnelle au Maroc (published by Horizons Maghrébins, 2000), the Moroccan tradition was already a long way ahead in these matters. The wool was soaked overnight in a mordant made of water and crushed bitter oranges, then bathed in a vat of water along with dried and pulverised madder roots. Once heated and washed, the wool emerged a garnet-brown colour.

Experts agree that cultivating madder requires a great deal of work and patience. It takes at least three years before the plant produces a root that can be used for dyeing. This slow production process certainly fulfils the criteria of sustainable consumption, but it will only attract a niche clientele.