[ad_1]

This is part 1 of a 4-part series

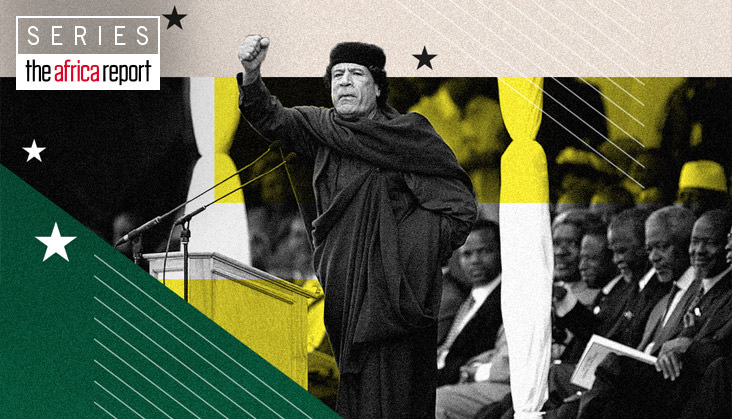

Kings Park Stadium in Durban, 9 July 2002. In what was the last summit of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and the first of the African Union (AU), the continent’s heads of state turned out in droves amidst a cacophony of vuvuzelas, military music and Zulu dances.

At the podium, flanked by amazons in uniforms, Gaddafi reminded his peers that it was his idea to replace a dying union with the new and pragmatic union which would pave the way for the ‘United States of Africa’. Had he not launched it in Sirte three years earlier? “We accept those who want to help us, but we don’t want those who wish to impose their own terms on us,” he added, before concluding with one of his favourite slogans: “African land for Africans!”

Wade, Mbeki, Mugabe, Mubarak, Dos Santos, Kabila, Gbagbo, Déby, Bongo, El-Béchir, Zenawi… Like the Libyan ‘Guide’, many of the leaders present that day have since left the stage, taking with them the promises of the dawn.

20 years later, the AU, which, in the words of a report by its Commission published three years ago, “has continued to imitate the European Union in terms of institutional structure and integration trajectory”, is far from achieving the results of its model – which is not necessarily the most suitable for the continent.

From non-interference to non-indifference

Compared to a largely discredited OAU, progress within the AU cannot be denied. Politically, the crippling approach of non-interference has been replaced by non-indifference, with condemnation of the principle of coups d’état and unconstitutional changes in governance.

The institutional overhaul led by Rwandan President Paul Kagame between 2016 and 2018 has resulted in strong proposals for operational efficiency, refocusing on fewer areas and proactive solutions to reduce the organisation’s financial dependence on foreign donors.

The launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) in 2019 is also to the credit of the AU, even if the implementation of this African common market, which must be ratified by all the parliaments of the member countries, presupposes a principle of free movement of citizens that is far from being achieved.

But when Africans are asked about the usefulness of the AU, the judgement is still harsh. Many see it as an ineffective organisation, which has not solved any of the problems for which it was created and whose objective is to outlast them.

Powerlessness

After all, wasting strength and prestige on intractable problems only serves to provide the world with an example of impotence, while pretending to do so provides a facade and maintains the illusion. The AU’s ultimate goal is to ensure its own survival, that of the officials who work there and that of the heads of state who sit on its board of directors as self-appointed agents of power.

A critical view perhaps, but whose fault is it, if not the heads of state, who are extremely reluctant to bolster the capacity of AU institutions and thus the credibility of the AU in the eyes of its citizens? They stubbornly cling to their summits, which are seen as the sole decision-making body, and are allergic to the slightest delegation of their sovereignty, while keeping a close eye on the chairperson of the Commission.

The result: a multiplication of institutions whose functions and utility Africans would be hard pressed to define, such as the Pan-African Parliament and its 200 or so deputies from national parliaments, plagued by internal conflicts and accusations of mismanagement, which is supposed to represent the AU’s consultative assembly; the Economic, Social and Cultural Council (ECOSOC), which brings together civil society organisations, associations and trade unions; the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights; the African Standby Force; and the Citizens’ Diaspora Directorate (CDD).

Empty shells

All these empty and costly shells, almost non-existent in the eyes of the populations they are supposed to serve and represent, are added to the list of stillborn projects (African Central Bank, African Monetary Fund) or projects which are struggling to emerge from failure, such as the Peace and Security Council (PSC) or the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), which are the subject of this month’s survey.

The solution for the AU to finally be credible and efficient, apart from the implementation of management reforms recommended by the ‘Kagame Commission’, does exist. But it means getting rid of the ‘elephant in the room’, namely the overwhelming influence of the Heads of State Assembly, which, as currently constituted, can – and does – override the executive, legislative and legal organs of the AU.

An AU led by a professional and independent commission, with ad hoc technical bodies, able to protect citizens and hold governments to account is the only way to restore the bond of trust between this mythical organisation and its 1.5 billion citizens. The fact remains that the elephant is in the room and does not intend to move.

[ad_2]

Source link