In France, two major African cultural events – ‘Africa 2020’ and ‘BD 20-21, Year of the Comic Strip’ – were scheduled to take place in 2020 and 2021, before a nasty little virus thwarted the plans of cultural institutions.

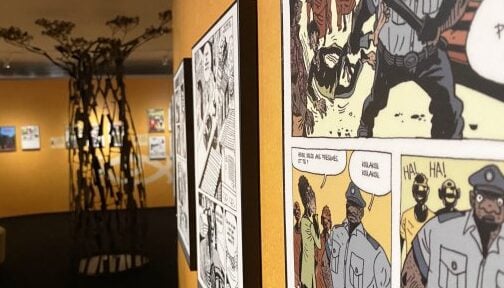

Museum closures have led to numerous programme changes, so it is only now that the exhibition ‘Kubuni, les Bandes Dessinées d’Afrique.s’ is finally opening at the Cité Internationale de la Bande Dessinée et de l’Image in Angoulême (until 26 September). At a meeting point between two major projects supported by the French government, ‘Kubuni’ offers a didactic immersion in the teeming world of the comic strip in sub-Saharan Africa.

“Since we started working on this project in 2018, we have discovered a new artist on the internet every day,” says exhibition co-curator Joëlle Épée Mandengue, the creator of the series La Vie d’Ebène Duta under the pseudonym Elyon. To launch ‘Kubuni’ (which means ‘imaginary creation’ in Kiswahili), it was therefore necessary to be restrictive in the selection process, in particular, by leaving out North Africa – which has already received significant media attention.

Pioneers of comics

The curators – Mandengue and Jean-Philippe Martin (adviser to the Cité Internationale de la Bande Dessinée et de l’Image) – thus opted for a chronological approach, highlighting the beginning of comics in Africa, their contemporary development and their future.

The first part of the exhibition provides a solid foundation for African comics by honouring pioneers. Although ‘narrative images’ on the continent predate the 20th century (bas-reliefs, appliqués, etc.), curators point to the pioneering work of Cameroonian Ibrahim Njoya (born around 1890), who was inspired by the tradition and history of the Bamoun royalty and worked on the ‘shu-mom’ alphabet developed at that time.

Adults in Cameroon are seduced by the words and references I use. They are astonished to discover that I have access to this anthropological knowledge.

His adaptation of the 1940s tale ‘The Spleen and the Four Rats’ is considered by the historian Christophe Cassiau-Haurie to be the very first Cameroonian comic strip. A little earlier, around 1915/1916, the Livingstonia Mission Press published a few issues of a humorous magazine in Malawi, the Karonga Kronikal, to entertain the British troops.

At the crossroads of influences

From the outset, African comics have been at the crossroads of influences between African traditions and Western dominance. The curators make this clear by bringing together – in the ‘pioneers’ room – the work of the Congolese artist Barly Baruti (born in 1959), Nigeria’s Tayo Fatunla (born in 1961 in England) and Frenchman Bernard Dufossé (1936-2016). From 1972 onwards, this international trio collaborated with the magazines Kouakou and Calao created by Pierre Rostini for French-speaking African countries.

For Gaspard Njock (born in 1985 in Douala), author of Maria Callas, l’Enfance d’une Diva (2020), Western comics have contributed most to the emergence of African cartoonists. “When I was a child,” he says, “I read the same authors as French kids, I had the same dreams. I didn’t even know African authors, their books were not available in French cultural centres.”

In their statement of intent, the curators write: “Colonisation, which imposed a form of cultural oppression on the dominated countries, certainly explains the aesthetic influence of comics in certain regions of the continent and the similarities from one country to another.”

The article continues below

Free download

Get your free PDF: Top 200 banks 2019

The race to transform

Complete the form and download, for free, the highlights from The Africa Report’s Exclusive Ranking of Africa’s top 200 banks from last year. Get your free PDF by completing the following form

“Countries under French or Belgian domination were often inspired by the likes of Tintin, the stories read in the comic strip magazine Pif Gadget or those offered in the ‘petits formats’. English-speaking regions were influenced by a very clear Anglo-American tradition, particularly that of the superhero genre. In addition to these external models, there is also manga, which is the result of the globalisation of Japanese popular culture.”

It would be a mistake to think that young African artists would simply fit into these moulds without trying to express their own individuality. The second part of the exhibition, which presents works as diverse as those of Annick Kamgang (‘Lucha’, 2018), Didier Kassaï (‘Tempête sur Bangui’, 2015), Koffi Roger N’Guessan (‘Les Fins Limiers’, 2016) and Loyiso Mkize (the ‘Kwezi’ series), confirms that African artists are working with all techniques and subjects and treating them in their own ways. Their freedom in cartoons seems almost greater than in other cultural or media fields.

Space for freedom

For Mandengue, ”creativity no longer has any boundaries, authors are free to tackle any theme. If I want to, I can travel other paths, explore other worlds.”

This is a point of view shared by Njock. “From the start, comics have always been able to take on all subjects. Flexible, skilful, not necessarily requiring a lot of resources, it can explore very broad fields. There are, for example, subjects that are controversial on the screen, such as homosexuality or migration, which are better dealt with through this medium.”

Social networks and the new means of communication make it possible to make oneself known, virtually, everywhere in the world.

The third part of the exhibition focuses on another space for freedom: the internet. It is no longer necessary to be published by a major European publishing house in order to exist. Social networks and the new means of communication make it possible to make oneself known, virtually, everywhere in the world.

This is what Reine Dibussi, author of the Afrofuturist series ‘Mulatako’, has done. “When I left school, I wanted to write a science fiction story for young people, with bright colours,” she says. “I didn’t get any response from French publishers, so I published the first six pages on my blog and chose to self-publish. Then, for volume 2, in association with the scriptwriter, we created a small company, Afiri Editions, to publish volume 2 in early 2021.”

‘Mulatako’, unbridled Afro-futurism

Mulatako is not designed to be distributed on tablets or phones, but some artists are embracing digital distribution. Many other artists, like Njock, remain fiercely attached to paper.

“I resist digitisation with all my might, even if it is an opportunity. I have a sensual relationship with paper that I don’t want to abandon. I like to get my hands dirty, feel the material, scratch the surface…” Unfortunately, visitors to ‘Kubuni’ will not really be able to experience this sensuality of the page: for economic reasons, the majority of the works exhibited are reproductions.

Saturated colours, an intentional use of inclusive writing, digital effects galore, bursting out of frames, lots of action and references to pre-colonial myths: Mulatako is a comic book that dares to be unbridled Afro-futuristic. Dibussi, its author, has not found a publisher, but she has self-published. “It all starts with a story I wrote as a teenager,” she says in her foreword.

It is a didactic investigation on the issue, a hot topic since President Emmanuel Macron’s speech in Ouagadougou, about the restitution of works of art looted in Africa during the colonial period.

“It was a science fiction story about me and my friends. A bunch of girls fighting the bad guys and saving the world. Yes, black and/or African female characters were so rare in artistic productions that I knew I had to create them. But the strength of Mulatako lies – above all – in references to the myth of the Miengu, commonly known as ‘mami-wata’.”

“Children are fascinated by this universe,” says Dibussi. “As for the adults in Cameroon, they are seduced by the words and references I use. They are astonished to discover that I have access to this anthropological knowledge.”

Property restitution in ‘La Revue Dessinée’

‘La Revue Dessinée’, created in 2013, is a quarterly offering that opens its pages to creators from all walks of life on topical issues. The shift, the distance and the perspective that drawing allows are exploited to give a pictorial, synthetic and constructed rendering. In the June 2021 issue, it offers a long report written by Hélène Ferrarini and drawn by Damien Cuvillier entitled ‘Privé de Retour’.

It is a didactic investigation on the issue, a hot topic since President Emmanuel Macron’s speech in Ouagadougou, about the restitution of works of art looted in Africa during the colonial period. The authors skilfully condense and investigate the major questions and contemporary developments around this issue. African demands, militant acts, French reluctance, legal advances, blind spots…everything is explored with precision and colour.

Queenie, the godmother of Martinique

Stéphanie Saint-Clair’s life reads like a novel. In Madame St-Clair, Reine de Harlem, published in 2015, novelist Raphaël Confiant tells the true story of this Martinican woman. Saint-Clair – ‘Queenie’ – landed in New York in 1912 and managed to establish her own criminal enterprise there, first independently, then by getting protection from Lucky Luciano.

Elizabeth Colomba (drawing and script) and Aurélie Lévy (script) have now joined forces to tell the story of Queenie’s violent and astonishing life in comics, as she made her mark in ‘the underworld’, in the heart of an ultra-violent male world. In a pure black and white style, ‘Queenie’ explores all the sides of her character, her childhood in Martinique, her pugnacity, her compromises, while offering many details on a dark period which also saw the growth and development of the civil rights movement.