[ad_1]

The extract, “Fluency and #MeToo” comes from Chapter 2 of Female Fear Factory, subtitled “Fear, Fluency and Control”, where I trace how women and other gender marginalised groups are socialised into the Female Fear Factory. Simply put, the Female Fear Factory is the global mechanism through which patriarchy regulates the world through fear, and the threat of violence against all women and other marginalised genders.

The Female Fear Factory rests on fear being understood as both a political, regulatory system and as a personal, intimate experience. Female Fear is repeatedly produced in public, in theatrical, spectacular ways. Repeated exposure is socialisation into the Female Fear Factory. Such socialisation works like the process of attaining fluency in language, when meaning can be transferred quickly, when there is no hesitation in decoding its signs or grammar.

In the passage, I spotlight an encounter between two powerful individuals fluent in the Female Fear Factory, but socialised into different roles within it: one as its target, the other as its heir.

Lupita Nyong’o’s behaviour is legible to readers from different societies across the globe: she wrestles with the scripts of deferred safety from gendered violence. Harvey Weinstein’s fluency guarantees him impunity to terrorise her (and many other women). At the time, it was inconceivable that safety from the consequences of patriarchal violence could be snatched away from Weinstein.

I chose it as an illustration of the Female Fear Factory’s reach, at the same time as testament to the possibilities of its unmaking. The Female Fear Factory can feel overwhelming. Therefore, throughout the book, in addition to unmasking it, I amplify moments where its targets – in Nigeria, South Africa, El Salvador, Brazil, Kenya, Egypt, Britain, Holland, Saudi Arabia, India, the US and other locations – undermine it and loosen its stranglehold. This is one such moment. Happy reading!

Fluency and #MeToo (excerpt from Chapter 2: Fear, Fluency and Control)

In her New York Times piece on Harvey Weinstein’s sexual harassment of her, actor Lupita Nyong’o draws on years of conditioning as a young woman across three countries – Mexico, Kenya, and the US – to mediate her increasingly harrowing experiences with the powerful Hollywood producer. She reports following the various scripts offered to women to keep themselves safe. She details a series of encounters, starting with one which took place when she was still a student at Yale School of Drama. Weinstein tries to bully her into drinking “vodka and diet soda” by ordering one for her even after she has refused one several times, ultimately calling her ‘stubborn’. Although she is uneasy, she feigns a laugh when he calls her stubborn, something she repeats later when he calls her stubborn again, this time after she refuses his offer of a massage when she arrives at his house following an invitation to view the film there, and discovers that he has other plans. Although she writes about this evening, saying “For the first time since I met him, I felt unsafe”, she is careful in how she rebuffs him. Part of this carefully orchestrated avoidance of his unwanted advances is to get away safely, rather than further endanger herself.

When he calls her stubborn again, she says: “I agreed with an easy laugh, trying to get myself out of the situation safely.” Nyong’o recalls going through a series of rationalisations to avoid naming her experiences with Weinstein as violence or sexual harassment, even as she decided she “would not be accepting any more visits to private spaces with Harvey Weinstein”.

Because the lessons of the Female Fear Factory are so enduring, they require both hyper-vigilance from women and second-guessing of the knowledge of being in harm’s way, despite following all the ‘rules’.

Nyong’o would bring a friend to the next encounter, and then an agent. However, Weinstein continued the campaign of harassment – which she characterises as increasingly crude – even after his apology at the Toronto Festival screening of her successful 12 Years A Slave movie in 2013. About his approach to her after she wins an Oscar in 2014, she says: “Harvey would not take no for an answer”, and regarding his behaviour at the Cannes Film Festival, she says: “I ran out of ways of politely saying no and so did my agent. I was so exasperated by the end that I just kept quiet.” Her “survival plan was to avoid Harvey and men like him at all costs”, as a way to deal with the sense of isolation she felt.

That’s why we don’t speak up – for fear of suffering twice, and for fear of being labelled and characterised by our moment of powerlessness

Indeed, Nyong’o mentions both fear and shame, pointing to their entanglements in how she responded to Weinstein’s sexual harassment, hostility, threats, and bullying. Explaining her motivation for penning and publishing Speaking Out about Harvey Weinstein in the final months of 2017, she says: “What I am most interested in now is combating the shame we go through that keeps us isolated and allows for harm to continue to be done.” Later in the piece, she says: “That’s why we don’t speak up – for fear of suffering twice, and for fear of being labelled and characterised by our moment of powerlessness.”

These two statements are on the fear of being shamed for being treated badly, because women bear the brunt of their victimisation. Patriarchy sees women always blamed for sexual violation, for failure to act appropriately in order to avoid it, and for acting badly as a way of inviting it. In the longer narrative as mentioned above, Nyong’o performs all the dances taught to women about how to avoid violation in patriarchal societies. She smiles and feigns ease when she is made uncomfortable and in the face of masculine aggression from a very powerful man. She searches the faces of other women around him “for any indication that she too had been made to feel uncomfortable by this powerful man”, but notices nothing. Although the reason she sees nothing is likely because the other women are also feigning ease, and possibly searching her own face for the same and finding nothing, she reads the absence of evidence of other women’s discomfort around Weinstein as a reason to undermine her own sense of how he acts towards her. She refuses alcohol because, already uneasy around him, she knows that alcohol may weaken her physical response time, make her more vulnerable and a quick escape more difficult. She also knows that whatever happens to her, if she consumes any alcohol, that will be used against her and as part of the arsenal to shame her.

Fear and shame isolate, as Nyong’o knows. Although dozens of Hollywood women accused Harvey Weinstein of sexual harassment, bullying, and violations of different forms, Salma Hayek was correct in drawing attention to the manner in which Weinstein kept quiet as many white women accused him of a string of atrocities, reserving his most virulent denials for accusations by two women of colour – Nyong’o and Hayek.

His responses were specifically to the piece by Nyong’o under discussion, as well as to Hayek’s own ‘Harvey Weinstein Is My Monster Too’ in the New York Times (13 December 2017 edition).

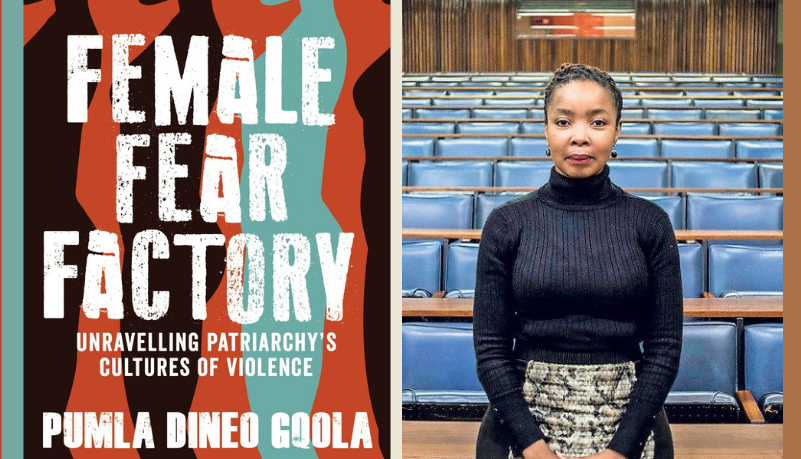

You can purchase Female Fear Factory: Unravelling Patriarchy’s Cultures of Violence at Cassava Republic or other online bookshops.

[ad_2]

Source link