From high-heeled shoes to TV sets, designer clothes to fava beans – goods looted from homes and businesses in wealthier parts of Sudan’s war-hit capital are now flaunted in some of its poorest neighbourhoods.

By the bus- and plane-load, about two million people fled Khartoum, and the adjoining cities of Omdurman and Bahri, after conflict broke out in April between the army and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Many criminal gangs – and some people who simply needed money – then broke into their homes, shops and factories, packing every conceivable item into boxes and baskets before walking back – or, in some instances, riding back on their donkeys – to their neighbourhoods on the edges of the capital.

The looting carried on for months and continues to this day, as law and order has broken down, with none of the police stations operating in a capital city wracked by daily bombing, shelling and shooting between the warring forces.

The ill-gotten wealth is on display in parts of Ombada and al-Thawra – poor neighbourhoods that the well-heeled of Khartoum were always hesitant to enter, partly out of fear of the armed gangs that operate there.

But most of the residents of Ombada and al-Thawra are honest people who come from the most-deprived communities of Sudan. They were not really in a position to catch buses or planes to another country, and stayed behind.

They have also become casualties of the war – 25 people were killed after shells fell in a district in Ombada, last month.

With no reliable data, estimates of the number of people who live in Ombada and al-Thawra vary from the hundreds of thousands to the millions.

Their homes used to be built of mud, wood and pieces of cloth, before being demolished by then-President Omar al-Bashir’s regime in the 1990s – and again in the early 2000s – as they were regarded as “irregular” buildings.

Eventually, most residents managed to build homes with bricks, though some mud houses still exist.

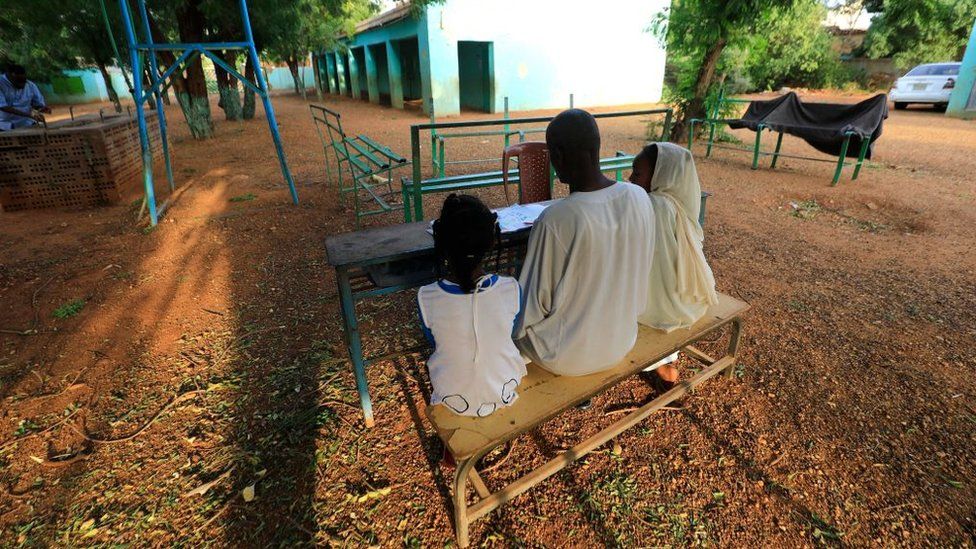

Education levels in these areas remain low – for instance, Ombada 19 district has only two schools, with each class having an average of 100 pupils. Most children drop out and are unable to read or write in Arabic, Sudan’s official language.

Children have nicknamed the schools Abook Dagas, Arabic for “Your father has been fooled” – a reference to the fact that they enrol with high expectations only to be disappointed because of the terrible learning conditions.

Almost all women in Ombada 19 and al-Thawara 29 are maids, or used to be maids, working for families in the wealthier parts of Khartoum, Omdurman and Bahri.

The maids who managed to climb up the social ladder became market vendors, selling basic items – like food and clothing – to earn a living.

Now more maids have advanced to the status of market vendor, selling the looted items at a very cheap price.

A digital TV, which normally sells for 150,000 Sudanese pounds ($250; £200), can be picked up for a bargain -10,000 Sudanese pounds.

Market vendors no longer sell cheap brands of fava beans, Sudan’s staple food, but the bigger and tastier ones normally served at the weddings of wealthier people.

Apart from homes and shops, huge warehouses have also been looted. One of them, packed with food products, was located behind the mountains of al-Markhyat in Omdurman.

It was emptied over several weeks, before being set ablaze in an act of wanton destruction. Black smoke rose over the skies of Omdurman for days.

One of the worst tragedies took place at a perfume factory, where about 120 people – including around 40 women and a few children – are said to have burnt to death.

Talk among residents of Ombada – which is about 3km (two miles) from the burnt-out factory – is that the place went up in flames as a young man was using his lighter to see as it was dark inside.

Some female looters were spraying themselves with perfume and packing them in baskets, while some of the men were only interested in taking the vats where perfume is stored – and were therefore pouring the perfume on the floor. The vats are used to store drinking water, which is in short supply because of the fighting, and so can be worth more than the perfume.

The lighter’s flame and the alcohol-containing perfume formed a combustible mix, causing a huge fire. When the blaze eventually died down, relatives went to recover the charred bodies, though some had turned into ash.

According to Ombada residents, only one person lived to tell the story – the brother of the man who lit the lighter – as he had gone outside, standing by the main gate when the factory went up in flames.

He expressed deep sorrow and regret, as he, along with other relatives and friends, mourned the dead in a city where war has made life cheap.