I recently met the award-winning writer Ubah Cristina Ali Farah at a literary festival on the Italian island of Sicily.

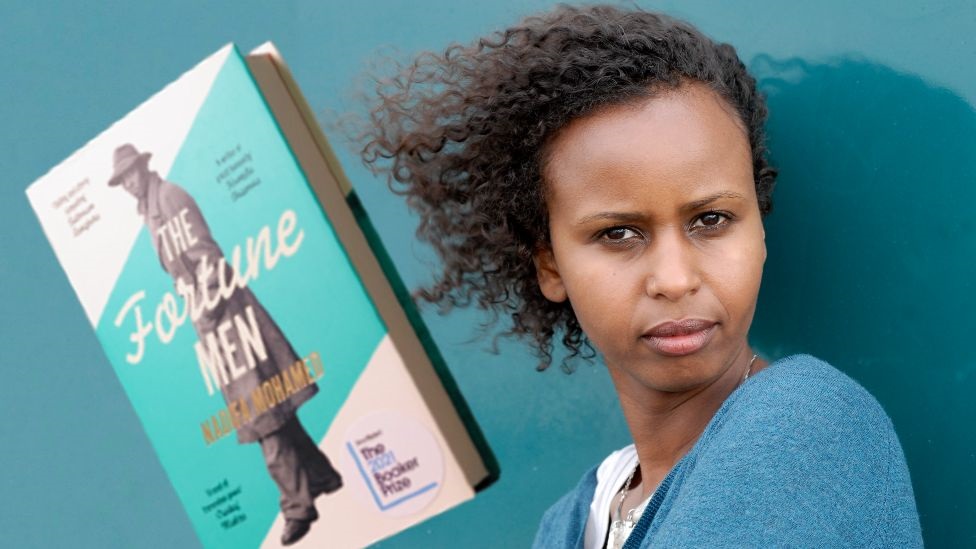

She is a member of a handful of globally acclaimed Somali female writers, including Nadifa Mohamed who was recently shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize for her third novel the Fortune Men.

For centuries, Somalia has been known as the “nation of poets” but this tradition has largely been the preserve of men.

It is unusual for Somali women to be the primary storytellers, yet they are now the ones taking on that mantle in the diaspora.

Ali Farah tells me this is because they have “more space” outside Somalia to pursue their literary ambitions – unshackled as they are from the cultural expectations placed upon them in a male-dominated society.

And what is more, their freedom to write comes from the fact that they are finding their voice in colonial languages such as Italian and English that they have made their own.ADVERTISEMENT

Forgotten voices

Ali Farah was born in the 1970s in Verona in Italy to a Somali father and an Italian mother.

Her father had left Somalia to pursue his education, and then returned home to build a new independent nation, taking his new family with him.

Growing up in Mogadishu, Ali Farah was educated in both Somali and Italian.

She was an avid reader and diligently kept a diary of her everyday encounters in the Somali capital.

In 1991, at the age of 18 and with a baby son, Ali Farah was forced to flee the escalating violence as the country descended into civil warfare, which continues to this day.

She first returned to Italy but now lives in Belgium.

Hundreds of thousands of Somalis fled – and their experiences inspired her to write – especially about the stories of women.

She says they have a special “memory” of what happened as they were often on the frontline of the conflict.K StanworthMy main questions were: ‘What happens when everything you are born into has been destroyed? What do you do to root yourself again? What do you do to survive?'”Ubah Cristina Ali Farah

Novelist

She wrote, she says, so that Somali women would not be “forgotten”.

“My main questions were: ‘What happens when everything you are born into has been destroyed? What do you do to root yourself again? What do you do to survive?'”

Her first novel, Little Mother, published in 2007, centres on two female cousins who are separated and eventually find each other in Europe.

On a personal level, Ali Farah found that writing fiction was a way to root herself again in a foreign land.

For centuries Somali was a spoken language, only becoming a written one with a Latin script in 1972.

This influenced its literature – poetry was recited, memorised and passed down the generations.

So novels have only really come into fruition in exile, though they often nod to Somalia’s rich oral tradition.

In Little Mother there are sensory layers of rhythm and tempo, mimicking the poetic form.

Ali Farah says it includes three classic poems reworked and imagined through the eyes and sounds of women.

Arranged marriages

The author is in Palermo, Sicily’s capital, to promote her new book Le stazioni della luna (Phases of the Moon).

Set in the 1950s when Somalia was under a UN Trusteeship, it is about the struggle for independence – and she takes her inspiration from the godfather of the Somali novel, Nuruddin Farah (no relation).

He wrote From a Crooked Rib in English – it was published in 1970 to international acclaim.

It centres on the story of Elba, a young female pastoralist who escapes an arranged marriage, running away to Mogadishu where she finds herself again subjugated by men.

Ali Farah’s names her main character after Elba. “It’s a tribute to Nuruddin,” she tells me.

But her Elba escapes to a more emancipated world with modern possibilities for Somali women.

“Literature is a dialogue with other texts and novels,” Ali Farah explains – a conversation between the past and present.

She also explores conversations between the men and women through her work, something that is all too often sadly missing in Somali society.

Her success – and that of her literary peers – has made it clear that Somali women will no longer be silenced.