Issued on: Modified:

The arrest of the parents of a 12-year-old Egyptian girl who died after undergoing genital mutilation and the doctor who performed the procedure highlight the difficulty of eradicating the increasingly medicalised felony practice.

A 12-year-old girl died in the Assiut governance of Upper Egypt last week due to complications she suffered after a retired doctor removed part of her genitals, a practice known as female genital mutilation (FGM), also sometimes referred to as female circumcision.

“The doctor tried to save her but she passed away,” the public prosecutor’s office said in a statement issued late Thursday, vowing “firm action” against anyone carrying out the procedure in the future. The girl’s aunt was also detained.

FGM was outlawed in Egypt in 2008 and was upgraded to a felony in 2016 after a 17-year-old girl bled to death. The updated law mandates jail sentences of up to seven years for those who carry out the procedure and up to three years for anyone requesting it. Religious leaders have also said genital cutting is forbidden.

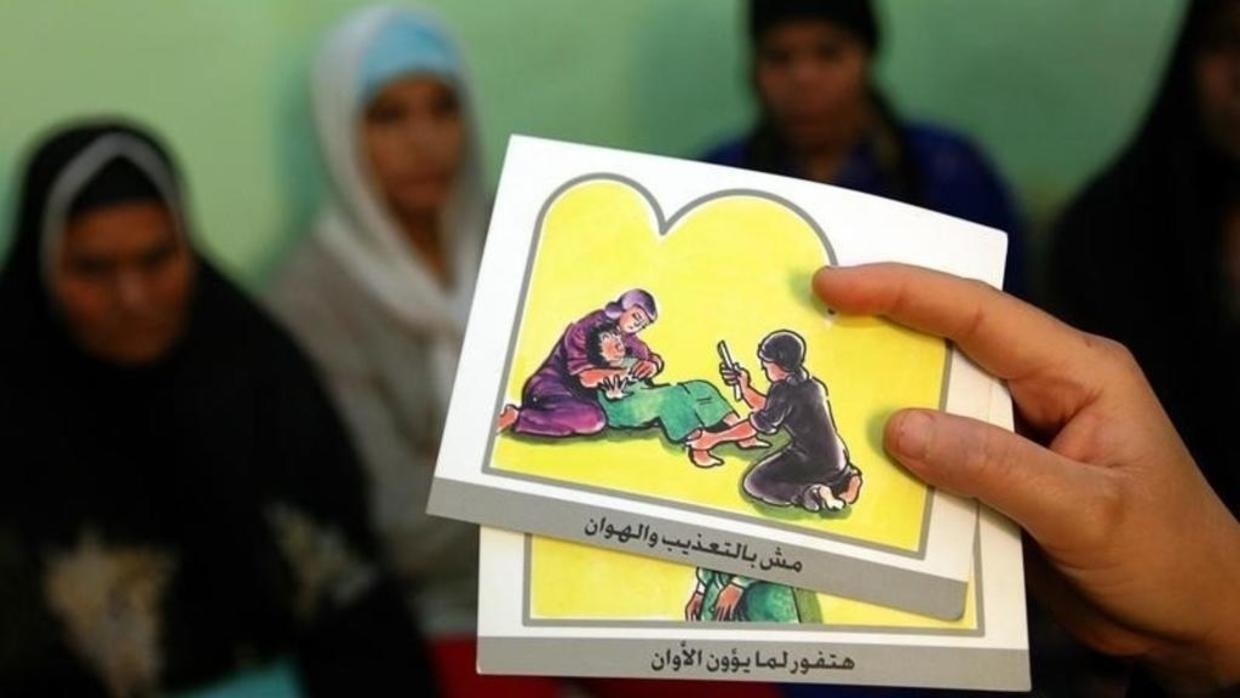

The government regularly runs public service campaigns to warn of the danger of FGM, but instead of curbing the practice the campaigns have prompted parents to turn to medical personnel to do it, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) said in November. “About 75 per cent of female genital mutilation in the country is performed by doctors,” FGM expert Dr. Ayman Sadek said in the UNFPA statement.

The medicalisation of FGM brings with it a new set of challenges, lending the appearance of legitimacy and safety despite the practice having no medical benefits and significant risks—including haemorrhage, chronic urinary problems and complications in childbirth.

Indeed, the girl in Assiut, whom local news sources identified as Nada Abdul Maksoud, underwent the procedure in a clinic where it was performed by a retired doctor.

Parents and practitioners are often not punished for the crime, activists say, but in Maksoud’s case women’s rights groups expressed outrage and pushed authorities to take action.

FGM generally involves the removal of the labia but can also include sewing up the vaginal opening and cutting or removing the clitoris. Diminishing sexual pleasure, it is viewed as a way to assure that girls remain pure. In rural areas in Egypt, husbands ask that their young brides undergo the procedure before marriage. More than 40 percent of respondents in a 2014 survey said they believed the practice prevents women from committing adultery.

Egypt continues to have one of the highest rates of FGM in the world, with 87 percent of girls and women between the ages of 15 and 49 having been genitally cut, according to a 2016 survey by UNICEF.

Reda Eldanbouki, executive director of the Women’s Centre for Guidance and Legal Awareness, said that judges and police often treat the perpetrators of FGM cases with leniency. “Most of them do not take the cases seriously because they believe that it is for the benefit of the girl to undergo female circumcision for the protection of her chastity,” he said.

Despite the most recent prosecution, authorities have largely failed to take clear measures that would eliminate FGM. For starters, the law has loopholes, according to Eldanbouki, criminalising the practice only in cases where there is no medical justification. “This clause opens the door to parents as well as physicians to claim that they were not conducting female circumcision but simply removing allegedly discomforting skin growth,” he said.

Until authorities on all levels take the crime more seriously, little is likely to change, activist say. “Many more Egyptian girls will be forced to undergo the procedure, and many of them will die — as long as there is no clear strategy from the state and a true criminalisation of the practice,” said Amel Fahmy, managing director of Tadwein Gender Research Center.

Globally, at least 200 million women have been subjected to FGM, according to UNICEF. FGM is prevalent in 30 countries, in which at least 30 percent of girls under the age 15 have been cut, according to United Nations statistics. The UN hopes to eradicate the practice by 2030. February 6 is the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation.

Source: France 24