South African bioinformatics expert Professor Tulio de Oliveira is still deciding whether to travel to New York City next month to accept his Time Magazine 100 most influential people award. De Oliveira keeps a tight schedule. Just back from Stockholm, where he addressed the world’s top COVID scientists at the Nobel Symposium of Medicine, he led the team that in 2020 first detected the Beta variant of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. De Oliveira and his team also detected the Omicron variant last year.

“So it was 26 scientists, invited from around the world to Stockholm,” says de Oliveira. “The main scientists who identified the virus created the vaccines, evaluated all the main therapies, identified variants, and run the best vaccine clinical programmes in the world.”

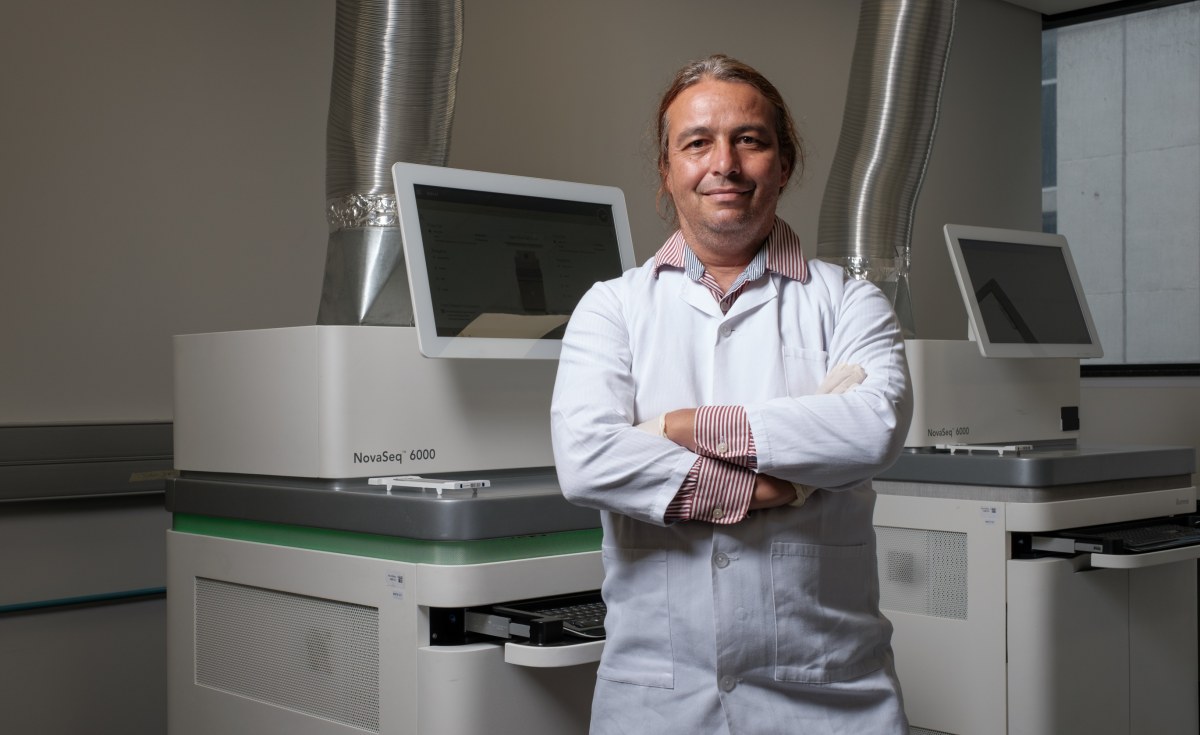

Seated in “meeting room 2” – an outdoor bench flanked by lemon trees next to the South African Centre of Excellence in Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis (SACEMA), housed in a restored Cape Dutch building in Stellenbosch – De Oliveira is dressed in knee-high shorts and a K-Way jacket. The man who heads the state-of-the-art local laboratories that first identified Beta and Omicron – Stellenbosch University’s Centre for Epidemic Response and Innovation (CERI) and the KwaZulu-Natal Research Innovation and Sequencing Platform (KRISP) – has a surprisingly unaffected demeanour. Hair tendrils escape his ponytail as he laughs.

Behind the variant discoveries

Speaking to Spotlight, De Oliveira, in his Portuguese accent, recalls the detail of their discovery. “We run a very effective, what we call the Network for Genomics Surveillance in South Africa [NGS-SA]. When we find anything new, we can transport hundreds and hundreds of samples from hundreds of clinics in South Africa, to all the main labs that can do quick genomic surveillance. I run the two main ones, both KRISP and CERI.

“What people don’t understand is that finding the first genome [the complete set of genetic information in an organism] is not difficult. The more difficult thing is to validate that this is a variant of concern, very quickly. And that’s what we did very well with the Omicron.”

KRISP, CERI, and the Botswana-Harvard HIV Reference Laboratory, all released the first Omicron genomes on Tuesday, November 23, 2021.

“At that time I was sitting in Durban,” says De Oliveira. “I just sent a WhatsApp to everyone saying ‘guys, I think that’s a new variant’. And then everyone stops everything. And we meet, a very senior group of people. It’s almost like a commando team, a SWAT team [Special Weapons and Tactics], you look to each other, and everyone knows exactly what to do. Okay. You go there, you do that. Everyone is very well trained, they have received the best training in the world.

“It was emerging in Johannesburg. So I asked the heads of the two big labs there – one is based at the University of Pretoria, the other one at the University of Wits – and the samples arrived less than six hours later, to our labs,” he says. “We received the samples at 6:00 am on the 24th. And by the end of that day, we had all the genomes analysed.

“Thursday morning, the 25th, we presented to our two ministers, Blade Nzimande [Minister of Higher Education, Science, and Technology] and Joe Phaahla [Minister of Health]. Then we talked to the President at 10 am.”

How did President Cyril Ramaphosa respond?

De Oliveira laughs. “Oh the President, I’ve talked to him many times. Half of the time he goes ‘not you again, Tulio!’ He said ‘that’s not good news. But it is better for us to be transparent, otherwise, it will leak to the media very quick. Better that we give all of the information quickly’. So by midday, the health minister had called for an urgent press briefing. He chaired that and asked us to present the information. On Friday, we had an urgent meeting with the World Health Organization,” De Oliveira recalls.

Hunting viruses amid stigma

Initially dubbed by some “the South African variant”, Omicron rapidly globally became the dominant variant of the virus, identified in 87 countries within three weeks. Its discovery resulted in stigma and animosity, with world leaders closing their borders to South Africa and local scientists even getting death threats.

“However, it soon became clear that although the variant was discovered in South Africa, it did not originate here, and the safety measures seemed more punitive than preventative,” says De Oliveira. “They were absolutely unnecessary and ineffective.”

Over the years De Oliveira (46) has worked on global viral outbreaks including HIV, Hepatitis B and C, Zika, Yellow Fever, Dengue, and Chikungunya. Reflecting on the COVID pandemic, he says: “The pandemic was a terrible thing from a health point of view, also from an economic point of view, and psychological. But at a scientific level, it was phenomenal how we could identify a new emergent virus within days and then develop diagnostics, develop vaccines, and tracking the vitals in real-time.”

In April, de Oliveira noted the discovery of two new Omicron sub-lineages on Twitter: “New Omicron BA.4 & BA.5 detected in South Africa, Botswana, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, and UK… No cause for alarm as no major spike in cases, admissions or deaths in SA,” he wrote.

In a piece published in the medical journal The Lancet last week, he calls for global health leaders to recognise – instead of punishing – researchers in Africa.

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, the lives of many loved ones and colleagues have been lost,” he writes.

“Despite the terrible toll of COVID-19, in South Africa scientists have worked relentlessly to produce some of the science that has driven the global COVID-19 response. But researchers faced challenges, notably the international travel ban that was placed on South Africa for much of the pandemic and deeply affected the local economy. Some researchers in South Africa received death threats and, at some point, even needed armed guards in front of our laboratories.

“It is time,” he says, “to enter a new global phase where researchers in Africa are recognised and not punished for their scientific discoveries. Scientists in Africa and other LMICs [lower middle-income countries] have key contributions to make in advancing global health, especially in areas such as epidemic response and infectious diseases.”

Young, gifted, and Brazilian

De Oliveira was born in Brasília, the capital of Brazil. His family later moved to Porto Alegre, where he was placed in a programme for gifted children when he was six years old. Here he would learn about computers and programming. He received his first 16KB RAM computer from his uncle when he was ten years old – one that still used a television as a screen.

He recalls his roots. “My mother, Maria Joao, an architect and civil engineer, was originally from Mozambique. She was involved in the freedom movement there. She went to Brazil because it got very dangerous with the civil war, she basically went into exile. And then the day that Mandela became president, she arrived at dinner and said ‘we are going back to Africa’. She knew that the war would finish in Mozambique because it had been funded by the apartheid government. So she went back to Maputo to take some big positions at the United Nations to help reconstruct the country. Me and my two sisters, we went to university in Durban.”

De Oliveira completed a PhD at the University of KwaZulu-Natal [UKZN], before studying further at institutions including the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom. Today he is a Professor at UKZN and Stellenbosch University, and an Associate Professor at the University of Washington in the United States.

Despite his titles, De Oliveira likes to be called by his first name. He prefers small towns to cities and regularly rides his bike to work from his home in the Stellenbosch suburb of Brandwacht. His wife Astrid works at Stellenbosch University’s Africa Open Institute for Music, Research, and Innovation. They have three children.

Monkeypox

On monkeypox, De Oliveira says: “Yes, it is another emergent virus. So at the moment we just got a paper with a colleague from Oxford accepted in The Lancet Infectious Diseases. We are part of a global collaboration that’s tracking it in real-time. So far it is a fast-moving epidemic. By today [May 27, 2022] I think there were over 250 cases in 25 countries. We just produced the graphic.”

He scrolls on his phone, enlarging a graph on the screen, adding: “We don’t think that it’s going to become global, affecting everyone. But it’s the first time that these large outbreaks happen in so many countries at the same time. Also, with monkeypox, it is very unusual to have direct transmission between humans. Normally it goes through intermediate hosts, which normally are rodents or squirrels.”

He gestures at a nearby oak tree. “Yes people don’t realise, but they are a natural host of monkeypox. The little beautiful squirrels that we have here.”

It’s a Friday afternoon and he has another meeting after our interview. “I’d rather be drinking wine,” he says, laughing.

Recognised by Time

De Oliveira was nominated for Time’s prestigious annual 100 most influential list in the “pioneers” section, alongside his former PhD student, Dr Sikhulile Moyo, director of the Botswana-Harvard HIV Reference Laboratory in Gabarone. Moyo obtained his PhD in medical virology in 2016. Others on the Time 100 list for 2022 include Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky.

On its website, Time states: “Scientists in Africa have been monitoring and sequencing pathogens since long before the pandemic. The world benefited from this network when scientists including Sikhulile Moyo and Tulio de Oliveira identified and reported on the emergence of the Omicron variant last November. It was a transformational moment and a shift in paradigm… “

A first for South Africa, Stellenbosch will host the Physics Nobel Symposium on “predictability in science in the age of artificial intelligence” in October, with De Oliveira set to address delegates.

Source link