Image copyright

Image copyright

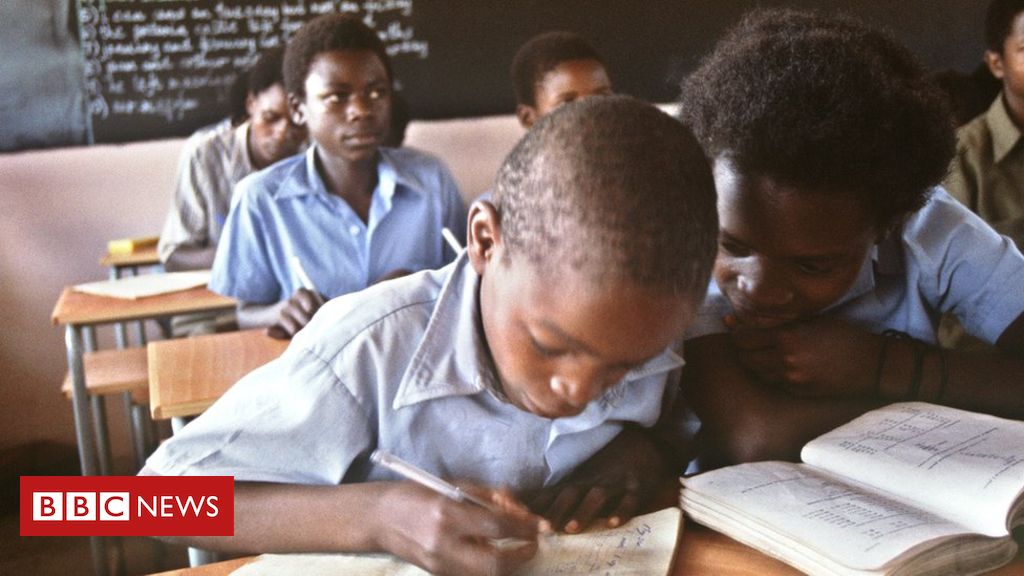

AFP

Many schools opened up in Zimbabwe after independence in 1980

Parents in Zimbabwe could face up to two years in jail if they fail to send their children to school.

The government has made education compulsory up to the age of 16 to stem rising school dropout figures blamed on the poor state of the economy.

It is estimated that in some parts of the country 20% of children do not go to school.

The new law also makes it is an offence to expel children for non-payment of school fees or for becoming pregnant.

Last year at least 60% of the children in primary school were sent home for failing to pay fees, according to the state’s Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVac).

Zimbabwe’s first leader Robert Mugabe, a former teacher who died last year, was praised for the education policies he adopted after independence in 1980.

The school system he established gave black Zimbabwean greater access to education as hundreds of state schools were opened, leading to Zimbabweans enjoying among the highest literacy rates in Africa.

However, free education ended in the 1990s and in the following decade the education system began to crumble.

What has changed?

The education law has been amended to make sure children in Zimbabwe go to school for a total of 12 years, five years more than was previously prescribed.

Image copyright

AFP

State schools are also suffering from a shortage of resources

Parents are now also in the firing line if their offspring fail to go to school.

They face up two years in jail – or a $260 (£200) fine if they can afford to pay it – if their children are found not to be attending classes.

The BBC’s Shingai Nyoka in the capital, Harare, says it seems to be a bold attempt to force parents to prioritise education during an economic crisis.

But some believe the government is shirking its responsibilities amidst broken promises to provide free basic education and a chronic shortage of state schools.

The high drop-out rate has also been blamed on pregnancy, early marriages, the long distances to schools and a lack of interest, our reporter adds.

Why are children dropping out?

By Shingai Nyoka, BBC News, Harare

Parents have been spending less on education as they struggle to buy food. Fees at government-run schools must be paid up front and range from between $30 (£23) and $700 a year, depending on where they are based.

Image copyright

AFP

Unregistered schools don’t insist on school uniforms

Last year, parents spent a third what they did in 2018 on education, says ZimVac.

In a sign of the desperate times, makeshift schools in poor areas of the capital, like Epworth, have been sprouting up in homes and backyards. They are unregistered – and therefore illegal. They can work out cheaper – about $3 a month – though their main draw is their flexibility about when the fees are paid.

Eunice Maronga, who runs one of these schools, says the children bring in money if and when they can. They are also more flexible about uniforms, though a $3-education has its drawbacks: no desks and one textbook – for the teacher.

“The reason why there is an increase in unregistered schools is because of the shortage of government schools – to the tune of about 2,000 schools,” says Liberty Matsive, from the non-governmental organisation Education Coalition of Zimbabwe.

Elizabeth Chibanda, whose children are at home after her food-vending business collapsed, says she has sent her eight-year-old daughter back to her home village.

“She is doing nothing in the village, but I was ashamed to have a grade-three student sitting around, when it’s so obvious to everyone she should be in school.”

Ms Chibanda said she was unable to get her son, who is six, into grade one at the start of the school year in January: “With my son, I can pretend he is not of school-going age yet.”

Why is the economy is such bad shape?

Mr Mugabe was ousted from power in November 2018 with the hope that his army-backed successor and former deputy, Emmerson Mnangagwa, would help revive the economy.

Image copyright

Getty Images

About 89% of adult Zimbabweans can read and write – among the highest literacy rates in Africa, according to 2014 World Bank data

But things have gone from bad to worse – and a decade on from the hyperinflation that devastated the economy, Zimbabwe is again facing rampant inflation, frequent shortages of foreign currency, food, fuel, electricity and medicine.

The country, which was once a major food producer, is also currently in the middle of a drought.

Last week, the US extended sanctions against Zimbabwe’s top leaders, citing their actions to “undermine democratic processes or institutions”, persecuting critics and economic mismanagement.

President Mnangagwa has blamed sanctions for crippling development in the country.

But Washington says their economic impact is limited to the farms and companies owned by about 80 of the targeted individuals, who include the president.

You may also be interested in:

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Source: CNN Africa