l

Singer Charli XCX and MP Priti Patel are among the British Asians descended from Indians who fled from Uganda in 1972. Tens of thousands came to the UK – but it’s a story many have never told. Until now.

It’s been 50 years since Uganda’s ruler, dictator Idi Amin, told about 70,000 Asians living in the East African country they had just 90 days to leave.

Many Indians had been brought to Uganda in 1894, while it was under British rule, to build railways.

Those who remained went on to become dominant figures in the country’s economy – something Idi Amin resented.

Roughly 30,000 Asians, most of whom had British passports, came to the UK. Many of those who came over faced difficulties and sometimes physical harm while trying to flee.

Some also faced racism upon arrival as they tried to rebuild their lives from scratch in Britain.

Today, Ugandan Asians have built successful businesses and futures for the next generation, but many have still not talked to their children or grandchildren about what they faced.

Now, on the 50th anniversary of their exile, young people are asking their elders what happened.

ADVERTISEMENT

‘Leaving to escape’

BBC Asian Network presenter Ankur Desai, who presents radio documentary Uganda: The Story Your Parents Never Told You, only really spoke to his mum Mrudula in the past year about her life growing up in Uganda.

She says the order to leave “came just all of a sudden overnight”, and people hadn’t taken it seriously at first.

“They were saying that one day Idi Amin dreamt in his sleep that he wants to get rid of all the Indians from Uganda,” she says.

“But then after a couple of days, they noticed that it was becoming serious and then the military over there were hassling our people quite a lot.

“Coming to the airport was becoming very difficult. The military were stopping them, beating them up, stealing whatever they were getting.

“Jewellery, money – everything.

“Everybody was leaving just to escape,” she says.

But Mrudula has fond memories of her time before Amin’s order.

“I can never forget the life in Uganda. We would have had the best of life, if the 90 days’ notice would not have been given,” she says.

Hearing what his mum and family went through has been eye-opening for Ankur.

“The more questions I asked, the more I learned about the challenges their generation faced,” he says.

But he also heard about “how they turned their fortunes around”.

“Their grit and determination is a lesson to us all when we face adversity,” he says.

“My parents worked tirelessly to give me a platform of relative privilege compared to the obstacles and barriers they had to overcome.”

‘We came here blindfolded’

Sanjay Dattani’s dad Sunil came over from Uganda when he was still in primary school. He then got jobs in factories and worked as a bus driver.

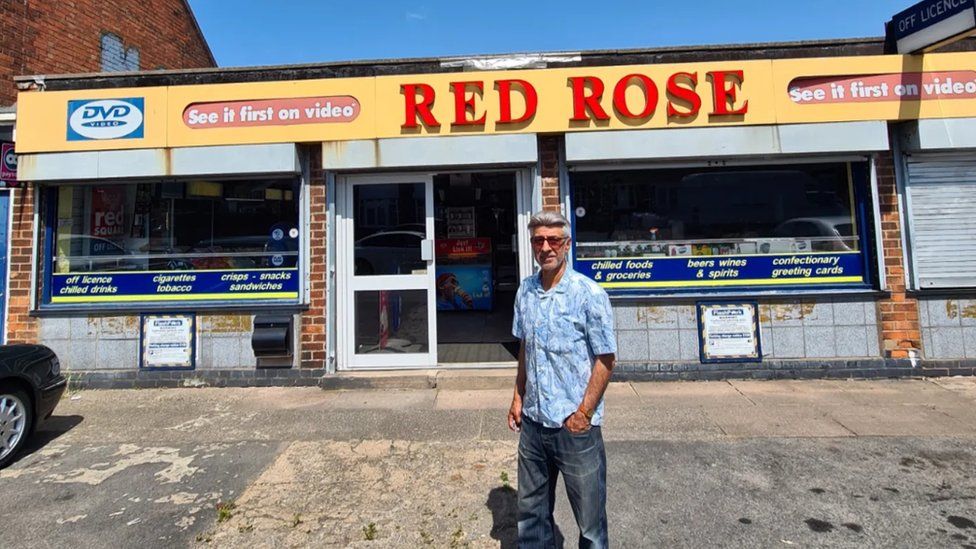

Ugandan Asians are said to have an entrepreneurial spirit, and in 1981 Sunil was able to open his own business in Leicester – a wedding photo and video shop called Red Rose.

It is now a convenience store.

Sunil always knew he wanted to set up a business, because that’s what his father did when he migrated from India to East Africa.

“Looking at him do business in Uganda, I had in my mind that one day I’ll be a business man,” says Sunil.

But it hasn’t always been easy to do, Sunil says.

“We came here blindfolded. It was difficult, difficult times, difficult place to live in. We had a house where two families were living with nine children.”

In 1972, Leicester City Council issued a notice in a Ugandan newspaper urging people “not to come to Leicester”.

Sunil did experience racism when he arrived in the UK, but is sympathetic to how residents were feeling.

“I guess it was it was new for them as well. How come all these Asians are here?” he says.

Despite all the difficulties his dad faced, Sanjay says it’s “in our blood to create businesses and to just try and find a way to thrive no matter what.”

‘A part of all our histories’

Twenty-nine-year-old Vanisha Sparks says she had “no idea of my roots, specifically of my Ugandan side of things,” for most of her life..

Mum Jyoti was among the first 2,000 Asians to arrive in the UK when she landed with her family.

They were initially kept in a settlement camp at RAF Stradishall in Suffolk, before being placed in housing in other parts of the UK.

Vanisha and her mum went to visit the site, now a prison.

“I can’t imagine being forced to leave everything behind,” Vanisha says.

“It’s like when people talk about if your house is on fire, and what few things would you take.”

After hearing her mum’s story Vanisha wants there to be more awareness about what Ugandan Asians went through.

“The locals around here don’t realise this prison actually used to be a camp for an Asian community who literally came over and had nothing in their pocket,” she says.

“There needs to be more commemoration of what happened.

“It’s not just a Ugandan Asian story. It’s a story that should run through Britons today because it’s part of all of our histories,” says Vanisha.

‘Africa is in your blood’

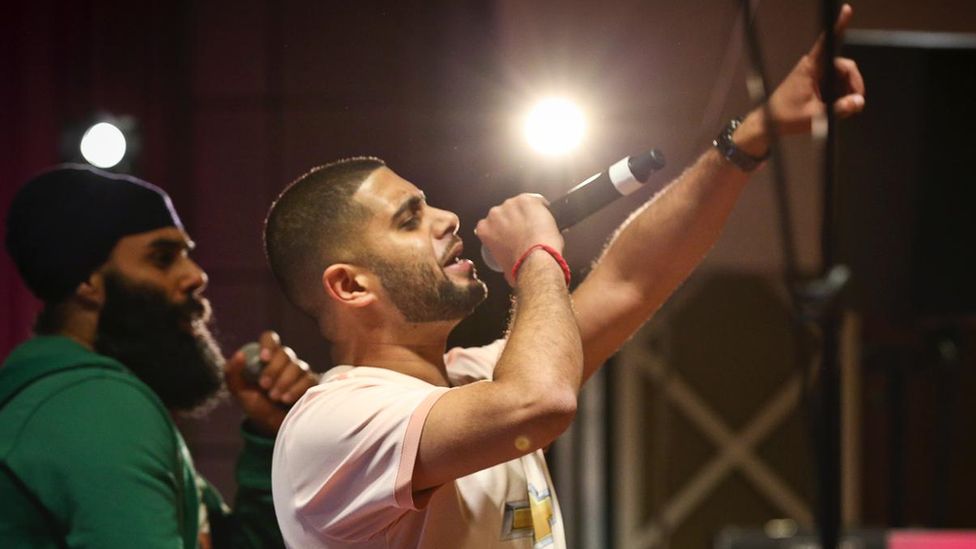

Rapper Premz’s mum is from Uganda and his dad is from Kenya.

“When I was younger, I just knew they came from there, which used to confuse me because I was like: ‘I thought we were Indian, though,'” he says.

Premz says family members who remain always tell him “Africa is in your blood” but it’s hard for a lot of people to understand his background.

“When I tell people that I have a mum who’s from Africa, they’re like: ‘Nah, you’re not black’,” he says.

In 1997, Premz says, some of his family members decided to take Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni up on his offer to return “home”.

“They rebuilt the businesses and are still there, and very happy and prosperous,” he says.

Hearing his parents’ stories about coming over has given Premz a different perspective.

“I just have a different type of admiration for it because I used to think I’m a hustler,” he says.

“But I’m obviously not to that standard. Like what they went through, it’s different.

“It was the hardest and worst thing, for what happened in Uganda then to happen.

“But it looked like a lot of people really kind of turned it into sugar when they came here.

“They really made the best of a bad situation, because a lot of people from East Africa have done really, really well considering they came here with absolutely zero.”

‘I realised I had no clue’

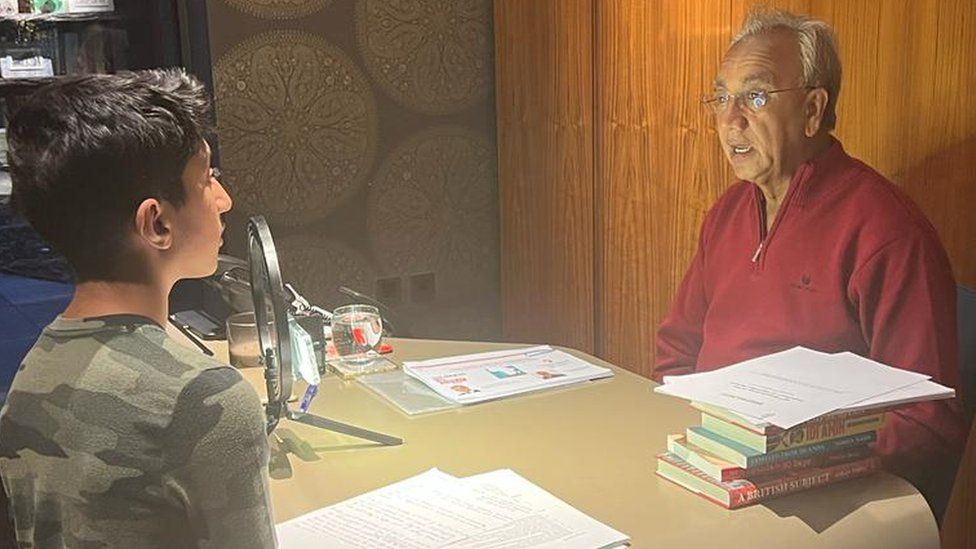

At Haberdashers’ Boys School in north London, 14-year-old Rudra Sachdev was tasked to do a project on something he cared about.

He chose Uganda.

“In my family at home, we have so much African vocabulary, like foods that we eat from Africa, and I just wanted to know,” he says.

“Because I suddenly realised I had no clue about how my family was related to Africa.”

Rudra interviewed his grandparents and great uncles and aunts for his project. He’s turned their stories into a mini-documentary on his website and an Instagram page.

Some of the conversations Rudra had, in particular with his great grand-uncle were difficult.

“He was crying a lot. And it was really difficult to hear about it as well,” Rudra says.

“When they moved to England, they had nothing and just had to get on with it and lock it away somewhere and make the best out of it.

“So talking about it again, with me and my mum, it just unlocked all of the trauma that was there.”

Rudra wants people to continue to add their own stories to his website to continue the legacy.

“I think that the our grandparents and great grandparents have sacrificed so much for us to have a good life and good education.

“So I think that it is literally everyone in our generation’s duty to learn about their stories, and to understand the sacrifices they made.”

Hearing his family’s stories has also given him a new perspective on his own life, he says.

“Knowing that my family had to deal with such a hard time in 1972, it makes me feel like whenever I’m struggling with anything, that I can deal with it,” he says.

“My grandparents, were so resilient, they had nothing, and they were always able to bounce back.

“They just kept on getting on with it. It’s so motivational.”