Hawwa – the Arabic name for Eve – is a young adolescent in 1960s rural Benghazi. She survives multiple pregnancies after having been married off to Adam, a truck driver, and struggles for her freedom and reproductive rights.

This account in The Horse’s Hair, the acclaimed novel by Libyan academic and novelist Najwa Bin Shatwan, is none other than the original sin story, retold with dark humour by an unborn child narrator, who leads the reader through the parents’ tragic trajectories.

The book is reminiscent of feminist retellings such as Circe, the 2018 novel in which the American novelist Madeline Miller adapts Greek myths from the point of view of a sorceress normally depicted as a villain. Similarly, with her writing oeuvre, Shatwan revisits Libyan history from the 19th and 20th centuries through a female lens.

“Bin Shatwan’s descriptions of female writers specifically being subject to societal censorship in Libya suggests a woman writing is a revolutionary act,” writes journalist Orna Herr in the global literary magazine, Index on Censorship.

Shatwan is part of a growing number of Libyan women writers who are giving more room to a gendered point of view in literature. This marks an important change in the still small Libyan literary scene. By building complex female characters, a growing number of Libyan writers are quietly introducing their ideas of gender equality.

Traditionally Libyan literature was dominated by male authors, who used their own archetypes to describe historical crossroads and to understand their current reality. Notable examples are the Benghazi poet Khaled Mattwa, known for recounting legends and pivotal moments in history with a unique flair, and Alessandro Spina who delved deeper into Libya’s past through a series of novels that include, The Confines of the Shadow.

However, in recent years, female authors – either Libyan or Tripoli-born Italians – have stepped in, revisiting the country’s history from the 1900s onwards, from the point of view of female characters. They include Alma Abate examining the advent of the late despot Muammar Gaddafi through the eyes of Sara in Ultima Estate in Soul D’Amore, or Maryem Salama writing about interracial marriage in the 1900s with the voice of the young nurse Fatima in From Door to Door.

They are looking at history in a way that attempts to break down the treatment of women as inactive objects.

Safa Elnaili, an assistant professor in the Arabic department at the University of Alabama, spotted this trend while researching short stories published on a popular Libyan website called, Almostakbal.

She was struck by the central presence of women in these narratives, something new to the Libyan literary canon. “The discussion of these stories is through the position of the female character in the narrative in relation to family members, society, and socio-political context,” she said.

In the early years of Gaddafi’s rule in the 1970s, the new government set up a single publishing house. All authors were required to write in support of the authorities, and those who refused to do so were imprisoned, forced to emigrate, or had to quit writing altogether.

In 2013, two years after the start of the revolution that overthrew Gaddafi, Tripolitanian novelist and poet Maryem Salama wrote a poem using the image of kindling a piece of firework. Deprived of a structured publishing industry, she published it on her Facebook page. A few hours later, a friend commented, “Thank you. I still cry burning joy in a dead home.”

This image stayed with Salama, who has since used the allegory of a phoenix to refer to her country. “Libya is still being created. It is not yet that great bird rising from the ashes,” she said over a video call. “Libya, the land, is waiting for the Libyan people to take responsibility for becoming the great people of the great land. They must read, they must know, and they must act.”

Gaddafi’s erasure of culture

This process is particularly crucial in a country where Gaddafi rewrote Libyan history to fit his agenda. Aside from controlling the publishing industry, he eliminated any threat to his view of Libya as a homogenous Arab society. The Amazigh (a Libyan ethnic group) language and script, Tamazight, was banned and could not be taught in schools. Those attempting to promote Amazigh culture and rights were persecuted, imprisoned and even killed. This resulted in a flattening of cultural diversity.

“Gaddafi’s historical revisionism has created a black hole in the histogram … for Libyans,” said Tripoli-based publisher Ghassan Fergiani, who is in his 70s. “Ninety percent of Libyans were born either around the time or after Gaddafi came to power. His version of the history of Libya is that everything started only after he came to power.”

In the 1950s – the decade Libya gained its independence – Fergiani’s father, Mohammed Bashir Fergiani, opened three successful bookshops in Tripoli, while also founding the publishing company Dar Al Fergiani.

After Gaddafi rose to power in 1969, authorities shut down the business and the family emigrated to the United Kingdom. In London, Fergiani’s father dedicated himself to finding old editions and rare books from Libya and the Arabic-speaking world and reprinted them through his new company, Darf Publishing.

Among the writers his son publishes today is Salama. The 56-year-old – whose books centre on the position of women in Libyan society – has been hailed as a leading light in the new generation of female Libyan writers by reviewers internationally.

Salama explained that Gaddafi fostered a sense of insecurity among Libyans by conveying distorted information. Before Gaddafi, writers had a chance to naturally evolve, to advance, to adopt new methods of dealing with Libyan traditions and producing new, contemporary culture. “This natural chance was restricted by the fist of the big brother,” she said gravely. “We grew up in iron cages, not knowing more than what he wanted us to know, not able to move further than his instructions. Libyan women were those who took the most damage.”

She spoke over a video call, and as we talked, Salama gave me a virtual tour of the adjacent bookshelves. Her expression lit up when she picked up copies of her books in Arabic and English. “That’s not to brag,” she joked, “it’s just to show you what these books look like.” The author was juggling a book translation project with hosting a morning variety programme on a local radio station, as well as preparing a new radio show on literature.

Women in a changing Libya

When it came to women, Gaddafi’s messaging was conflicting. The flamboyant leader famously surrounded himself with female bodyguards dubbed “The Amazonian Guard” – referring to the mythological home of the Amazons in Libya – but these women were also reportedly harassed and abused by Gaddafi.

Gaddafi established military training for women in secondary schools, but according to Salama, who endured this instruction in her youth, it was not something he did to promote equality. Rather, she said, it was an excuse to exclude women from a proper education, as the military training was done at the expense of studying other topics.

In daily life, women in Libya faced many complications as a result of Gaddafi’s policies, said writer Mahbuba Khalifa, speaking via video call from her home in Tunis, in neighbouring Tunisia, where her family now lives after years of living abroad for security reasons. “The women in my country have doubled their efforts to be able to balance between their hope and aspirations, for themselves and their families, and the reality that cast shadows over them.”

Khalifa is a soft-spoken woman in her 60s. Wearing rimless glasses and neatly combed blonde hair, she sat on a brown sofa. Next to her, leaning forward with a sharp and resolute stare and her black hair tied up, was her daughter Rima, who is also her editor. Rima – one of her four children and a writer herself – has a straight-to-the-point tone, as she added details and context to her mother’s answers. “She was the one who encouraged me to share my writing with the world,” said Khalifa, looking proudly at her daughter, who nodded in agreement. “My mum had a treasure trove of stories to tell, but she didn’t give them the value they deserved. She needed someone to give her a push!” Rima explained.

Excavating Libyan heritage has been a lifelong passion for Khalifa. “It’s ancient, continuous, and motivating,” she said. She was writing a historical novel about her hometown, Derna, a port city in eastern Libya, which used to be one of the wealthiest regions. She left when she was 18 years old, but still feels strongly connected to it. The novel is about the suffering of the residents of Derna during the conflict between the Allies and the Axis in North Africa during the second world war. It included campaigns fought in the Libyan desert. She noted that inhabitants of coastal cities took shelter in caves in the mountains to avoid the aerial bombardments by the Allies, a fact that features in her book.

Khalifa also draws from memories of her own life. “Some were inspired by my constant moving from one place to another, within Libya or abroad. All this enriched my imagination.”

“The constant travelling was a necessity for us,” Rima explained. “My dad [Libyan politician and lawyer Goma Attaiga] was an opponent of Gaddafi’s regime, and we were forced to leave the country for our own security. Mum herself wrote for opposition magazines for years under fake names.”

Khalifa’s first novel, We Were and They Were, published in Arabic in 2021, was a great success among Libyan readers, and spread by word of mouth. It was autobiographical, she said, “I had a desire to give a testimony of a Libyan woman who lived through a certain stage in the country’s history and was affected on a personal level by some significant events.”

The loosely autobiographical novel charts her years as a student up until the fall of Gaddafi in August 2011. “My entry to the university coincided with the drastic changes that took place in Libya, as a result of the coup against the monarchy. My generation was an eyewitness to these confusing changes for us, the Libyan people, who were living at a calm pace back then.”

She recalled the times when oil had just been discovered, and there was hope for a prosperous future. “All this abruptly turned into a life of anxiety and fear of the new authority and the beginning of arrests and restrictions of liberties, as well as huge economic and social changes,” she said. Khalifa paused, as she thought of her husband’s arrest. “It changed forever the course of my own life for sure.”

Libyan history through feminist mythologies

Now, these female authors are adapting local folk tales, Greek mythology, and sacred texts. “There is an inheritance of historical fiction in Libya, which is natural, given the depth of Libya’s presence in the history of [the] Mediterranean, and the diversity of the peoples who inhabited or colonised it through different times,” noted Tripoli-based writer Kawther Eljehmi.

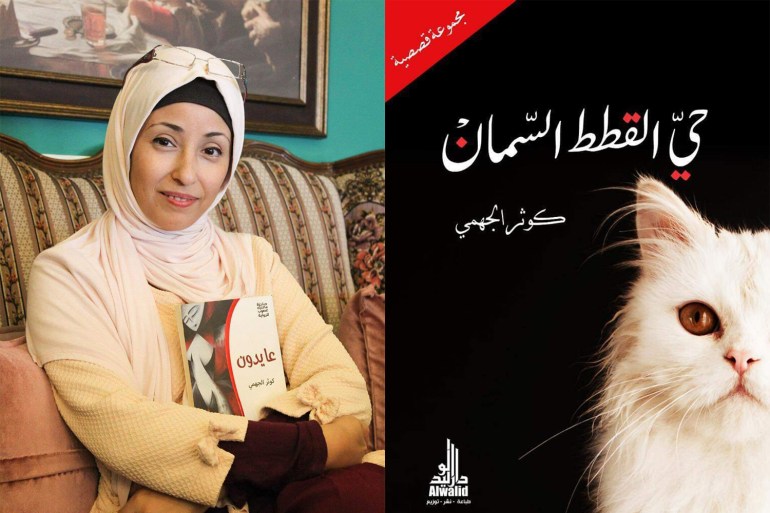

The 38-year-old spoke via video call from her home in Tripoli. Eljehmi is part of a generation of writers that emerged thanks to the internet. She had been blogging since 2016. After three years, she deleted her first blog, called Normal Lady, and reposted all her articles and stories on the popular Facebook page Fasila dedicated to Libyan writers. Through the internet, she gained traction and gathered a following, even before publishing her first novel, Aidoun, two years ago.

The instability of the country is the most serious issue that comes into play when she writes. “The process for my first novel was smoother. I wrote when I was pregnant with this little one,” she said in a mix of patience and playfulness, as her four-year-old, Moness, stuck his nose in the webcam. “But for the second novel, it was much harder to finish.” This was during the 2019 civil war. Eljehmi was living in an area that saw fighting. Bombs going off made establishing a writing routine “almost impossible”.

She managed to finish the book. Entitled, The Colonel, it centres on a fictional character who resembles Gaddafi. Eljehmi is already working on a new novel, which revolves around the issue of children born to Libyan women married to foreign nationals. These children are not entitled to free education and healthcare because they are not considered Libyans.

Italian writers on colonialism in Libya

Italian female writers have joined the historical reckoning, examining their country’s colonisation of Libya. Previously an Ottoman possession, Libya was occupied by Italy from 1911 until 1943. On December 24, 1951, Libya declared its independence. In 1970, Gaddafi ordered the expulsion of the country’s Italian population.

Here, mythology and the female gaze are once again the lenses through which Italian writers have examined the past. An example is Le Amazzoni, published last year by Manuela Piemonte. She explored the Italian-dominated Libya of the 1940s through the eyes of two little girls.

Piemonte worked in publishing and as a screenwriter before devoting herself to her first novel. The 43-year-old loves to research and gathered copious archival materials on her subject matter. As we talked via video call, she showed me, with hesitant satisfaction, a collection of fascist memorabilia that she collected in the service of literature: vintage books, fascist badges, and postcards. “I wanted to make sure I could describe every detail properly.”

The protagonists of Le Amazzoni are the daughters of Italian settlers in rural Libya, when Italy’s fascist dictator Benito Mussolini declares war on the country. They endure a period of estrangement from Libya by remembering the strong image of a Berber woman running in the desert on horseback, aspiring to become her.

“When I started to investigate the period of Italian colonisation to write, the Amazons came to me as a symbol of strength,” said Piemonte. “Only later, I discovered that Libya is precisely where the women warriors were located in Greek legends.”

Another period being examined by female Italian writers is the post-war era. The late Tripoli-born author Alma Abate told us in the novel, Ultima estate in suol d’amore, published last year, about a multi-ethnic Tripoli where Italians, English, French, Americans, Jews, Christians and Muslims lived peacefully side by side.

The same period was also explored in the fictionalised memoir, Il casa di Shara Band Ong: Tripoli, by Mariza D’Anna, 60, who dedicated previous books to the history of her family in Libya. “I wanted to share an experience that has been lived by many Italian children born in Libya, of being chased by the place they considered home,” she said over the phone from Trapani, Sicily, her home since being expelled by Gaddafi. The book came out last year.

D’Anna has a way of speaking of Libya as a place in between a faraway dream and something that belongs to historical accounts. “I haven’t had many literary exchanges with Libyan authors when I wrote the book, because what I wanted to encapsulate were just my memories,” said D’Anna, who was forbidden to go back to the country – being for years on Gaddafi’s blacklist as a Libyan-born Italian. “I’m aware that describing those years pre-Gaddafi as a very happy period can sound disturbing to some Libyans, who were probably living a radically different experience.”

But, she concluded, “This is the truth of what I remember.”