Dressed in protective gear and swinging a baseball bat in one hand, Daniel Gatimu, a client at the rage room, smashes glass bottles into smithereens.

At the sound of shattering glass, he feels a surge of relief.

In a world brimming with the relentless pressures of everyday life, a new method of stress relief has risen from the chaos.

Rage rooms, spaces designed for individuals to vent their frustrations by smashing and crushing objects, are booming in Kenya.

Gatimu prefers the rage room, a controlled space where he can release his anger, rather than taking it out on others in the outside world.

“Before I came here, I was super, super mad because of the economy, the femicide issue, how the government is running things, it’s really really not good and school. Yeah. I would say it’s better to be here than being out there being rude to people, shouting at people, throwing fits, yeah, so come here to relieve your stress in a controlled room,” he says.

In steps another client, Kinya Gitonga.

Before she can enter, she needs to wear the protective clothing and face masks – with so much splintering glass, protective gear is a necessity.

With every crush and every scream, Gitonga lets off steam.

“It’s been amazing, throwing the bottles and, you know, screaming, letting out my inner pain, worries, sadness. It’s been a wonderful experience. I’m feeling much better. My heart is not heavy anymore,” she says.

While discussing stress relief strategies with her friends, 23-year-old counseling psychologist Wambui Karathi explored different ideas.

Karathi points out that many Kenyans do not seek therapy because it has historically been framed as a service primarily for individuals with psychotic disorders.

This has created a stigma around mental health care, leading people to believe that therapy is only necessary for severe mental illnesses rather than for anyone experiencing stress, anxiety or personal challenges.

“But how therapy was introduced to us, there is a lot of discrimination and stigmatization around it. And it was introduced to us like it’s for people who are not okay in the head like mad mad people,” Karathi says.

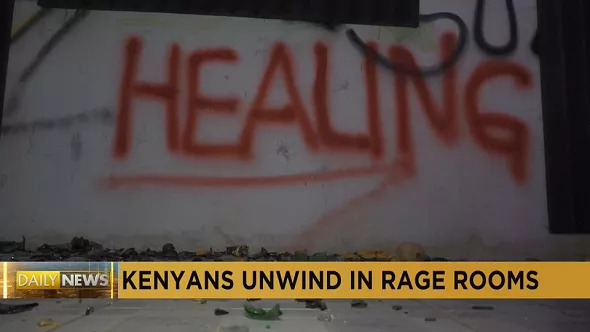

She was watching a movie with friends, and it featured a rage room – inspiration struck, and she founded the Healing Room, a space where individuals can access both therapy services and the opportunity to release their frustration in a rage room.

“So we started having conversations and remembering the different movies that we were watching. There is one that stuck out about rage rooms. When you’re going through a lot of things, you feel overwhelmed, like you want to just crush something and do anything. So that’s how the idea of the rage room started,” Karathi says.

Karathi established the Healing Room in September 2024 and has served about 40 clients at the rage room.

Karathi, however, emphasizes that rage rooms cannot replace therapy.

She explains that although a rage room may offer temporary relief for issues such as anxiety, it doesn’t address the root causes of the condition.

“Rage room itself, rather, it’s not a substitute for therapy. People need to go to therapy,” she says.

“The reason why it’s not a substitute to therapy it’s because with therapy you are able to deal with a root issue, root cause of whatever is going on with your life,” she adds.

According to a report by Global Mind Project, 23 per cent of Kenyans, or approximately 10.9 million people, are struggling or distressed with their mental health.

Furthermore, 75 per cent of the population does not have access to mental health services, with four people committing suicide every day, according to Kenya’s Ministry of Health.

The graffiti etched on the walls by her clients after each session gives an idea of the frame of mind of those leaving the room.

“Lives were definitely saved here,” reads one message.

“It’s all going to work out. Stay calm!” reads another.

After all the violence, the floor is awash with a sea of glass shards which will need to be cleaned before the next client.