At least 150 people were killed during two days of fighting in the latest ethnic clashes over land disputes in Sudan’s southern Blue Nile state.

The bloodshed is the worst in recent months and crowds took to the streets of Blue Nile’s state capital Damazin in protest on Thursday, chanting slogans condemning a conflict that has killed hundreds this year.

“A total 150 people including women, children and elderly were killed between Wednesday and Thursday,” said Abbas Moussa, head of Wad al-Mahi hospital. “Around 86 people were also wounded in the violence.”

Clashes in Blue Nile broke out last week after reported arguments over land between members of the Hausa people and rival groups, with residents reporting hundreds fleeing intense gunfire and homes set ablaze.

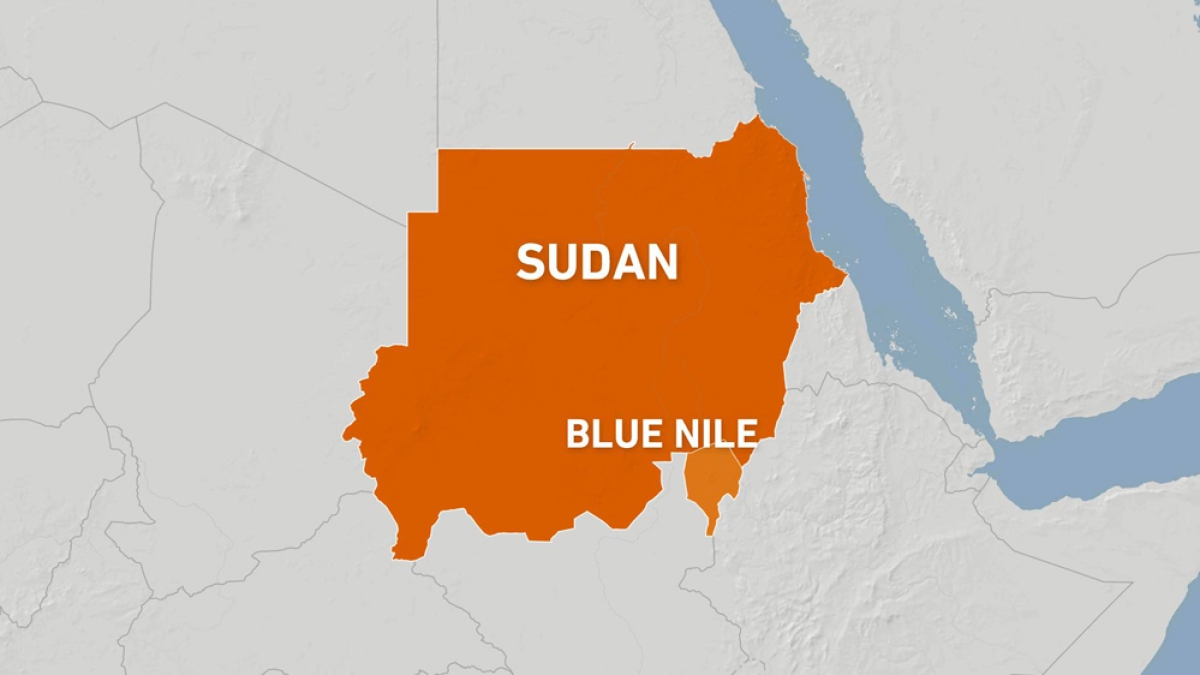

The fighting has centred around the Wad al-Mahi area near Roseires, 500km (310 miles) south of the capital Khartoum.

On Thursday, hundreds marched through Damazin, some calling for the state governor to be sacked. “No, no to violence,” the demonstrators chanted.

Eddie Rowe, the United Nations aid chief for Sudan, said he was “deeply concerned” about the continuing clashes, reporting “an unconfirmed 170 people have been killed and 327 have been injured” since the latest unrest began on October 13.

Blue Nile shaken by ethnic violence

Tribal clashes that erupted in July killed 149 people by early October. Last week, renewed fighting killed another 13 people, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

The July fighting involved the Hausa, a tribe with origins across West Africa, and the Berta people, following a land dispute. On Thursday, a group representing the Hausa said they have been under attack by individuals armed with heavy weapons over the past two days, but did not blame any specific tribe or group for the attack.

A Hausa issued a statement calling for de-escalation and a stop to ”the genocide and ethnic cleansing of the Hausa”. The tribe has long been marginalised within Sudanese society, with July’s violence sparking a string of Hausa protests across the country.

The Blue Nile is home to dozens of different ethnic groups, with hate speech and racism often inflaming decades-long tribal tensions.

OCHA had no confirmation of the latest surge in casualties but said the violence has displaced at least 1,200 people since last week.

Later Thursday, a grassroots pro-democracy group in Sudan known as the Resistance Committees blamed the country’s military rulers for what it said was a lack of security in the Blue Nile, accusing them of not protecting ethnic groups.

OCHA also said tribal clashes in nearby West Kordofan province, which broke out last week, killed 19 people and wounded dozens. A gunfight there between the Misseriya and Nuba ethnic groups erupted amid a land dispute near the town of Al Lagowa.

The West Kordofan state governor visited the town on Tuesday to talk to residents in a bid to de-escalate the conflict before coming under artillery fire from a nearby mountainous area, OCHA said.

“Fighting in West Kordofan and the Blue Nile states risks further displacements and human suffering,” OCHA said. ”There is also a risk of an escalation and spread of the fighting with additional humanitarian consequences.”

On Wednesday, the Sudanese army accused the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North, a rebel group active in the Blue Nile and South Kordofan, of being behind the attack on Al Lagowa. The rebel group has not responded to the accusation.

The violence in West Kordofan prompted around 36,500 people to flee Al Lagowa while many who remained sought shelter in the town’s army base, OCHA added. The area is currently inaccessible to humanitarian aid, the agency said.

Eisa El Dakar, a local journalist from West Kordofan, told The AP last week that the conflict there is partly rooted in the two ethnic groups’ conflicting claims to local land, with the Misseriya being predominately a herding community and the Nuba mostly farmers.

Much of Kordofan and other areas in southern Sudan have been rocked by chaos and conflict during the past decade.

Sudan has been plugged into turmoil since a coup last October that upended the country’s brief democratic transition after three decades of rule by Omar al-Bashir. He was toppled in an April 2019 popular uprising, paving the way for a civilian-military power-sharing government.

Many analysts consider the rising violence a product of the power vacuum in the region, caused by the military coup last October. The violence has also further threatened Sudan’s already struggling economy, compounded by fuel shortages caused, in part, by the war in Ukraine.