Artist Che Lovelace was on his way to the coast on the Caribbean island of Trinidad to collect mud to use in carnival celebrations when he received a message that a church in the UK wanted him to create an artwork to commemorate the life of an African man he had never heard of.

Quobna Ottobah Cugoano was a respected abolitionist in 18th Century Britain – but, despite his significant role in the abolition of the slave trade and slavery, his story is not that well-known.

Cugoano was born in the Gold Coast, today’s Ghana. He was enslaved when he was 13 – captured with about 20 others as they were playing in a field.

His destination was the sugar plantations of the Caribbean island of Grenada. On board the ship taking him across the Atlantic Ocean, there was, as Cugoano writes, “nothing to be heard but the rattling of chains, smacking of whips, and the groans and cries of our fellow-men.”

Forced to work on a sugar plantation after two years of “dreadful captivity… without any hope of deliverance, beholding the most dreadful scenes of misery and cruelty”, he was brought to Britain and managed to gain his freedom in 1772.

This is the only reliably attributed image of Ottobah Cugoano – from an etching done in 1784

The descriptions come from Cugoano’s own published book in which he argues against slavery, drawing on his Christian faith and his own experiences of the trade.

He was one of the Sons of Africa, a group of black Britons who wrote letters to British newspaper editors and members of Parliament to campaign against the slave trade and slavery.

The English Heritage site says it is not known how Cugoano gained his freedom, but it may be significant that in the same year he came to England, the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield, ruled that an attempt to send a formerly enslaved person back into slavery was unlawful.

On 20 August 1773, 250 years ago, at the age of 16, Cugoano was baptised John Stuart in St James’s Church Piccadilly, in the centre of London. But he published his book 13 years later under his original, African name.

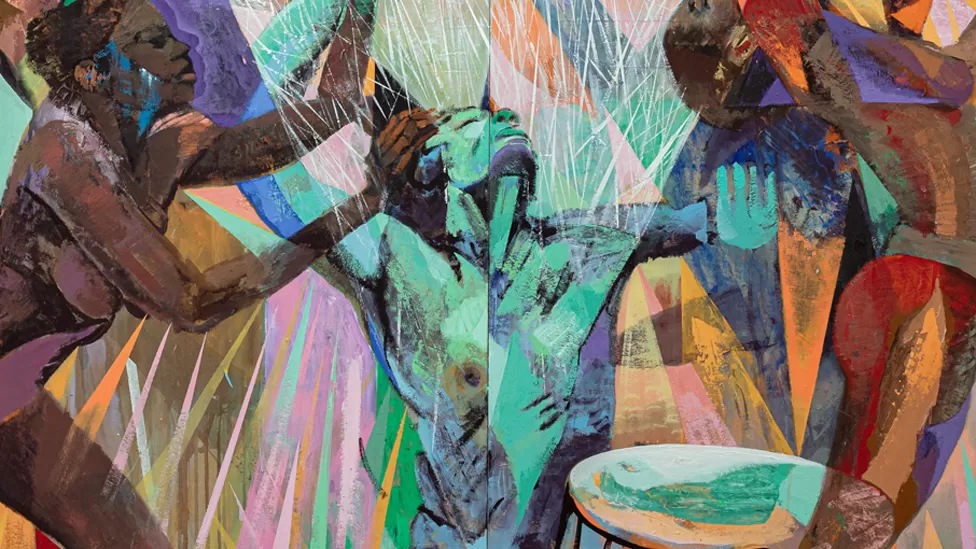

Lovelace’s artwork in honour of Cugoano is being installed in the church entrance on Wednesday, 20 September.

His work was “the most nourishing, exciting and appropriate for the space”, says the Reverend Lucy Winkett, the rector of St James’s Church.

Lovelace is an oil painter and uses rich colours and bold shapes, which joyfully and playfully depict, and are inspired by, the people and landscapes of his native Trinidad.

He tells the BBC he was surprised not to know about Cugoano because he thought he was well-informed about the abolition movement.

“I feel fortunate to be part of shining a light on who Cugoano was – and it makes me wonder about other hidden people and their stories,” he says.

This work consists of four paintings called River, Passage, Spirit and Vision of the Birds. Each painting is divided into four panels – something that the artist does in all his work.

“I worked on the panels simultaneously – moving back and forth between the various images and ideas and, of course, trying to imagine the entire piece as a whole.”

The idea for River came on the same day that the artist received the news of the commission – when he was collecting mud that is used in the rituals of J’Ouvert, the opening day of Trinidad Carnival. He was helped by men from Matura, the village in east Trinidad where he grew up.

“When we were finished getting the mud, the men were washing off in a nearby river, and that scene immediately resonated because of the cleansing and transformative powers of water,” Lovelace says.

“There was something quite special and serendipitous about getting the news of the commission where I was at the time.”

The second painting – Passage – depicts a female figure underwater and is also a reference to the “middle passage” – the journey across the Atlantic Ocean endured by millions of enslaved Africans, including a 13-year-old Cugoano.

“I used the image of a total submersion in water to suggest an out-of-body experience – something magical and suspended. And it is a homage both to the people who survived this trip, as well as those who did not.”

The Lovelace paintings are the first permanent artwork commissioned by St James’s Church Piccadilly – known as the “Artists’ Church” because many artists either worshipped or were baptised there.

This includes poet and artist William Blake, who was a contemporary of Cugoano – and one of Lovelace’s favourite artists.

The Anglican church has a long-standing relationship with the Royal Academy of Arts – they are both on Piccadilly, on opposite sides of the road.

Lovelace’s paintings capture “a sense of emerging out of water into a new tomorrow”, Rev Winkett says – much like what the act of baptism symbolises.

Lovelace says that he approached the commission in a similar way.

“I imagined this as being akin to a baptism, or a rite of passage,” he says.

Che Lovelace says the fragmented, patchy history of the Caribbean is an influence on his style

Interestingly, when Lovelace was a baby, an Anglican church in Trinidad refused to christen him Che, the name he goes by. His official name is Cheikh Sedar – Cheikh after the Senegalese historian-philosopher Cheikh Anta Diop and Sedar after Senegalese poet and first president Léopold Sédar Senghor.

Lovelace – who studied art on the French island of Martinique – set up studio in Trinidad in the mid-1990s. He loves to experiment with his paintings and his style does not really fit under any school of art.

This latest work – commemorating Cugoano’s life and legacy – is another layer in the artist’s attempts to “stitch together the complexity of Caribbean life”.

“Che’s work not only connects with the geographies and legacies of the abhorrent Transatlantic slave trade,” Rev Winkett says, “but also evokes an honest, lyrical, sun-filled exaltation of what a vibrant future with open acknowledgement of these histories might look like.”

Lovelace tells the BBC: “I still keep thinking of this difficult, unlikely journey that Cugoano had to endure.

“Quite possibly the only way forward towards equitable societies, where wounds heal and more promising futures are imagined, is by being more honest about the past.”