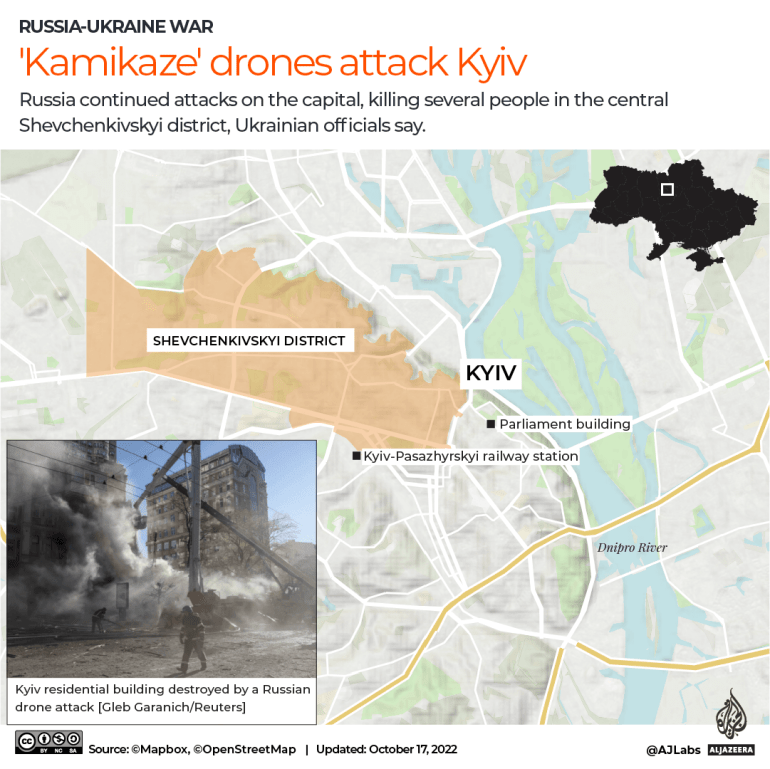

A little before 7am on Monday, people in Kyiv heard a whining sound overhead before identifying where it was coming from – a group of “kamikaze” drones flying into the city.

Drones have been widely used on both sides of the Ukraine conflict, but these were the first Russian attacks that deployed swarms of the aircraft.

Videos and images began to circulate on social media of the drones flying directly over urban infrastructure such as power stations, residential buildings and railways as civilians and soldiers tried to shoot them down with guns.

About 28 were launched on Monday morning in Kyiv. At least four civilians were killed after one of the aircraft hit a residential building.

Tension was high as locals waited to see where the drones would go. There was the low buzz of the aircraft, gunfire and screams as each of the drones still flying found and dove for its target.

The aircraft are called kamikaze drones because they attack once and don’t come back. Ukrainian officials say the ones primarily being used in their airspace are the Iranian-made Shahed-136. About 2,400 were apparently purchased by Russia in August, and their first reported use in Ukraine was a month ago.

They are far from top-end technology. The smallest costs just $20,000 while a traditional drone typically is at least 10 times that figure.

They also carry 35 to 40kg (80 to 90 pounds) of explosives, significantly smaller than most drones. But their value is in their numbers. They appear in large swarms and fly low enough to evade radar-defence systems.

“They’re relatively small, and they’re single use,” said Katherine Lawlor, a research fellow at the Institute for the Study of War. “They fly into something and then explode.”

“It’s important to note that these are not the kinds of drones that you see in other conflicts, such as US Predators, which are far more expensive and sophisticated,” she said. “These drones are effectively missiles – they loiter in place looking for their target.”

Their low price means the drones can be deployed in large numbers, and they hover before they strike, so they have a psychological effect on civilians as they watch and wait for them to strike.

Ukrainian officials estimated they have shot down dozens in the past week and nearly 100 since they were first used. But even if they are shot down, they explode in the air and can spray potentially deadly debris. Those that hit their target detonate on impact.

The emergence of swarms of drones in Ukraine is part of a shift in the nature of the Russian offensive, which some speculate indicates that Moscow may be running low on long-range missiles.

Russia has recently intensified its aerial bombardment of densely populated urban areas, such as the capital, Kyiv.

Analysts say this appears to be in retaliation for recent Ukrainian attacks, such as the bombing of a bridge linking Russia with Russian-occupied Crimea, as well as an attempt to demoralise the Ukrainian population and fighters.

But this strategy also potentially signals a wider trend worldwide.

“These drones allow Russia to target Ukrainians far away from the front line, away from the primary battle space,” says Ulrike Franke, a senior policy fellow at the European Council for Foreign Relations who leads its Technology and European Power Initiative.

“But it’s not just a tactic to target civilian populations and infrastructure. It’s also about depleting Ukrainian air defences,” she said. “Every drone shot down is another shot from Ukrainian defence systems – whether people or weapons – that can’t be used against something else.”

Suicide drones

Like many trends of modern warfare, these techniques appear to have been tested during the decade-long war in Syria, where both Russia and Iran have reportedly used suicide drones.

Unlikely countries are also becoming international drone heavyweights, such as Turkey, which has recently been selling drones to countries such as Somalia, Nigeria and Albania that are locked out of the traditional military marketplaces.

Ukrainian forces themselves have used Turkish-made Bayraktars along with US-supplied Switchblade drones.

With many countries unable to purchase high-cost drones favoured by the US and other Western powers, these kinds of smaller, cheaper drones are likely to be more widely deployed.

Members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps have reportedly been dispatched to a military base in Crimea to help train Russian forces how to use them.

“There’s been a lot of debates between experts about whether drones will be used in more advanced fights, like a potential US-China conflict,” said Zachary Kallenborn, a policy fellow at the Schar School of Policy and Government who researches unconventional weapons and technology. “These examples [in Ukraine] are evidence that drones will be used extensively even by more advanced military powers.”

“We’re seeing the military value in using large amounts of mass drones,” he said, “so a logical response would be ‘Well, how do we make this more effective? How can we integrate this with other communications, make it more dynamic, make it more precise?’ The technology is certainly going in a direction where these are the future of war.”

There are indications Ukraine’s military and the civilian population are already adapting to the new challenge presented by these throngs of drones.

As Ukraine’s forces wait for shipments of missiles and other air defence systems, a Ukrainian start-up has partnered with the Ukrainian military to develop a smartphone app called ePPO Observer, which allows civilians to supply targeting data for Ukrainian forces.

Ukrainians can report sightings of incoming aircraft and missiles through the app.

“Calmly go to the ePPO Observer application, select the desired category, then point your smartphone in the direction of what you saw or heard and press the big red button,” a press release said.

Reports indicate there will be blackouts and electricity rationing in Ukraine after these attacks took out critical power infrastructure. Iran has already agreed to ship more drones and missiles to Russia despite condemnation from other countries and Ukrainian politicians.

With fighting still raging in other parts of Ukraine, it is unclear whether sheer volume alone can swing the conflict in Russia’s favour, particularly on the battlefields further away.

“The use of these swarms of drones is intended to have a psychological effect among Ukrainian civilians as well as decision-makers on the ground,” Lawlor said. “But it’s not going to change much on the front line.”