[ad_1]

No matter how technologically sophisticated an election management system, it will not produce a nationally credible result without accountability, transparency, and political will.

Those requirements are all the more critical when it is reckoned to be the closest election in the country’s history. Like justice, credible elections must be delivered and to be seen to be delivered.

That cause wasn’t helped at the national election centre on 15 August. Thousands of eager voters had descended on the Bomas cultural centre in Nairobi to hear the presidential results.

Long musical interludes from several local choirs failed to lift the mood of the crowd as word spread of disputes about the results.

Officials delayed the announcement multiple times when party activists threatened to disrupt proceedings, claiming their leaders had not been shown the final roster of validated results.

Then riot police moved in to throw out protesting party officials. Diplomats left hurriedly. Just before electoral commission chairman Wafula Chebukati was due to announce the official winner of the presidential, it emerged that his deputy, Juliana Cherera, along with three more of the seven election commissioners had refused to sign the final results.

Cherera and her colleagues held a press conference on the other side of the city. They said they could not “take ownership of the results” because of the “opaque manner” with which the results had been handled.

‘Hero of the election’

These complaints followed reports of tensions within the commission between Cherera and her colleagues, all appointed last September, and the old guard around chairman Chebukati who had presided over the disputed elections in 2017.

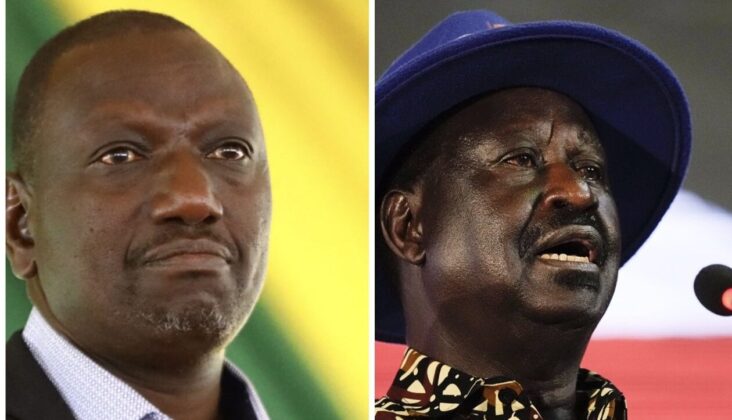

Pointedly ignoring Cherera’s complaints, Chebukati pressed ahead with his announcement at Bomas that Deputy President William Ruto had won the presidential election with 50.5% of the vote against former Prime Minister Raila Odinga with 48.9%. Raila had boycotted the ceremony, waiting until the following day to announce he would petition the Supreme Court to annul the election.

Ruto thanked Chebukati, proclaiming the commission to be the “hero of the election”. Later he told journalists that it was “… the most transparent election in the history of this continent” and dismissed out of hand the complaints by the dissident four commissioners.

Petition in motion

The case set out by Cherera and her colleagues is likely to be key to the petition against the election results by Raila. Much may depend on the interpretation of the rules governing the commission. Can Chebukati, as chief returning office, announce results without securing support from a majority of his fellow electoral commissioners?

Also key to the assessment of Raila’s petition will be evidence from the commission’s chief executive Marjan Hussein who was confirmed in the post in March. He recruited over 500,000 election workers and took on much of the procurement.

Raila and his party have until 22 August to present their petition, after which the Supreme Court has two weeks to assess it. If the court annuls the election, the commission has 60 days to organise a second round.

Déjà vu

At a time of worsening economic conditions and authoritarianism in the region, the case will test party loyalties as well as public support for the court.

It comes in the wake of disputed elections in Kenya in 2007, 2013 and 2017.

Horrendous clashes after the 2007 elections, killing over 1,200 people and chasing over a third of a million from their homes, were followed by a shaky pact between the elite but the sponsors of the violence were never held to account.

It prompted more political reforms culminating in a new constitution devolving power from the centre to 47 counties as well as strengthening the independence of the judiciary.

Ruling on the elections in 2017, the Supreme Court tested its new won independence and annulled the results. It lambasted the commission for failing in its constitutional duties and proposing far-reaching reforms for the body.

Tensions ratcheted up when the Deputy Chief Justice’s driver was shot in Nairobi. The commission’s Chief Executive Ezra Chiloba was dismissed but few substantive reforms were made.

Police reported no progress in their search for the killers of the commission’s information technology director, Chris Msando, whose mutilated body had been discovered two weeks before the elections in 2017.

- Msando had irritated some in the political establishment after he had pledged to run a clean election.

Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee blamed the commission’s failures in 2017 on a combination of willful incompetence and internal sabotage. It called for all implicated senior officials and commissioners dismissed.

The commission’s chairman Wafula Chebukati stayed on, overseeing preparations for this year’s elections. A few senior officials resigned but it was far from the wholesale clear out that parliament had demanded.

Handshake pact

Much of the pressure for reform and more openness at the Commission dissipated when the two main protagonists of the 2017 election, President Uhuru Kenyatta and former Prime Minister Raila Raila, agreed what they called their handshake pact.

The deal ended with Kenyatta renouncing his support for his Deputy William Ruto as his successor; and instead supporting Raila. That roiled the government, putting Kenyatta at loggerheads with Ruto.

It also side-lined calls for change at the electoral commission.

Raila had lost interest in reforming the commission, setting more store on his new alliance with outgoing President Kenyatta.

Ruto sternly defended the commission’s handling of the 2017 elections. He insisted that it was already highly effective and hired one of its computer experts for his campaign team.

Chebukati, whose term as commission chairman expires next year, bet heavily on bringing in high-tech election management systems.

The commission spent over $370m on printing ballots, information technology and biometric checks on voters. All this worked impressively, at least in technical terms.

Tallying votes

A day after voting on 9 August, the commission posted results from about 46,000 polling stations on its public portal. The idea was that journalists and civil society organisations would tally this information, constituency by constituency, and publish running totals of the state of play in the presidential polls.

As the commission’s officials were validating results in coordination with party officials, the main national media houses, together with the BBC and Reuters, were publishing provisional results showing the two main candidates, Raila and Ruto, running neck and neck.

Kenyans at home and in the diaspora followed the race avidly on radio, television, and social media. That mass scrutiny offered a check on the claims of rival politicians and some scrutiny of officials at the commission.

As the commission validated the results for each constituency, after painstaking cross-checks, an official would read out the figures at the election headquarters at the Bomas cultural centre in Nairobi.

Whatever the Court rules next month, it would be a wasted opportunity if this latest dispute didn’t also trigger a more considered review of governance and the procurement of hi-tech election management systems at the commission.

And then suddenly on 12 August, media organisations stopped publishing the data when they had tallied provisional results for 90% of the 290 constituencies. At that stage, Raila and Ruto each had about 49% of the vote.

It looked like a coordinated decision, but government officials deny pressuring the companies. Some journalists were wary of announcing an election winner based on the provisional count before the commission had validated all the results.

Behind the lines in the commission are vested political interests that the court may struggle to expose.

State security officials in Nairobi have been briefing civic activists about concerns over the costs and integrity implications in the commission’s technology procurement.

Part of the backdrop is the Directorate of Criminal Investigation’s (DCI) arrest of three Venezuelan election sub-contractors at Nairobi airport on 21 July. That triggered a spat with Chebukati accusing the police of harassing his employees. DCI Chief George Kinoti, a close ally of President Kenyatta, insisted the arrests were fully justified.

Other rows broke out over claims of surplus ballots being printed in Athens and a damning audit by KPMG which revealed multiple security breaches in the commission’s information system.

Both rival candidates claimed malfeasance in the run up to the vote.

Wasted opportunity if…

There is little chance the Supreme Court will have time to assess many of these issues in detail, so the petition is likely to focus on arguments claiming abuse of process.

Whatever the Court rules next month, it would be a wasted opportunity if this latest dispute didn’t also trigger a more considered review of governance and the procurement of hi-tech election management systems at the commission.

And as the dust settles on this election season, the commission will have to find ways to work with the parties, the media and civil society to create the highest public confidence in its operations.

[ad_2]

Source link