Algerians expected the elections to go off without incident and for President Abdelmadjid Tebboune to win a second term. Instead, they saw the president himself question the vote count and his opponents file legal challenges alleging fraud.

This surprising turn of events marks a turning point for Algeria, where elections have always been carefully choreographed by the ruling elite and the military apparatus that supports it.

The country’s constitutional court has until next week to rule on appeals from Mr Tebboune’s two opponents. But no one knows how the election issues will be resolved, whether the counts will be re-done, and what that means for Tebboune’s efforts to project an image of legitimacy and popular support.

The National Independent Authority for Elections (ANIE) released figures throughout election day indicating a low turnout. As of 5pm on Saturday, turnout was 26.5%, much lower than in elections five years ago. After unexplained delays, the agency reported that by 8pm, the “provisional average turnout” had reached 48%.

But the next day, she reported that only 5.6 million out of nearly 24 million voters had cast ballots, far short of 48 percent.

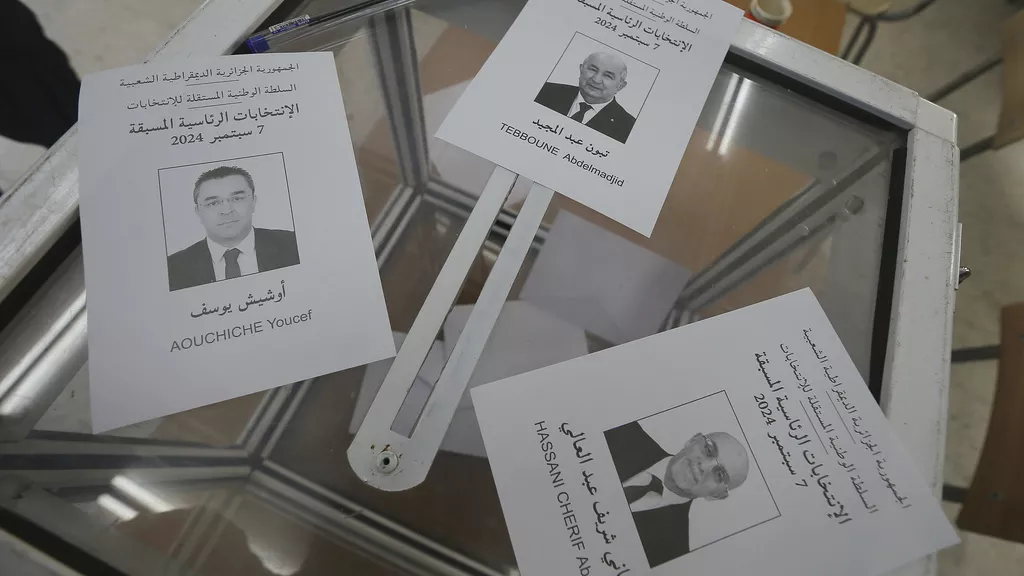

She said 94.7 percent of voters had voted for Mr. Tebboune’s re-election. His two opponents – Abdelali Hassani Cherif of the Movement of Society for Peace and Youcef Aouchiche of the Front of Socialist Forces – received only 3.2 percent and 2.2 percent of the vote, respectively.

Cherif, Aouchiche and their campaigns subsequently questioned how the results were reported and alleged fraud, including pressure on election officials and proxy voting.

None of this surprised observers.

But later, Mr. Tebboune’s campaign joined his opponents in issuing a joint statement accusing the ANIE of “inaccuracies, contradictions, ambiguities and inconsistencies,” thereby legitimizing questions about the president’s victory and associating him with the popular anger that his opponents had stoked.

Cherif and Aouchiche filed appeals with the Algerian Constitutional Court on Tuesday after their campaigns again denounced the election as “a charade. “

Participation rate

Turnout is notoriously low in Algeria, where activists see voting as endorsing a corrupt, military-run system rather than bringing about meaningful change.

Urging Algerians to participate in the election has been a campaign theme for Mr. Tebboune and his opponents. This is largely due to the legacy of the Hirak pro-democracy protests that led to the ouster of Mr. Tebboune’s predecessor.

After a caretaker government hastily scheduled elections in December 2019, protesters boycotted them, calling them rigged and saying they were a way for the ruling elite to choose a leader and avoid the sweeping changes they were demanding.

Tebboune, considered the military’s preferred candidate, won the election with 58 percent of the vote. But more than 60 percent of the country’s 24 million voters abstained and his victory was greeted by renewed protests.

His supporters had hoped that a victory with a high turnout this year would strengthen Tebboune’s popular support and put distance between Algeria and the political crisis that toppled his predecessor. That gamble appears to have failed, as only 5.6 million of the 24 million voters cast ballots.

Hirak protests

In 2019, millions of Algerians took to the streets in pro-democracy protests known as the “Hirak” (meaning movement in Arabic).

Protesters were outraged after President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, 81, announced his intention to run for a fifth term. He had rarely been seen since a stroke left him paralyzed in 2013.

The Hirak was jubilant but dissatisfied when Bouteflika stepped down and prominent businessmen were accused of corruption. The protesters never rallied around leaders or a new vision for Algeria, but called for deeper reforms to foster genuine democracy and remove from power members of what Algerians simply call “le pouvoir” — the business, political and military elites who they believe run the country.

Hirak protesters have dismissed Tebboune as a member of the old guard and interpreted most of his early overtures as empty gestures intended to appease them.

Before, during, and after Tebboune’s election, protests continued. Then COVID-19 struck and they were banned. Authorities continued to crack down on free speech and imprison journalists and activists made famous by the pro-democracy movement, although protests resumed in 2021.

Hirak figures have denounced the 2024 election as a rubber-stamp exercise aimed at consolidating the status quo in Algeria and called for a new round of boycotts to express a deep lack of confidence in the system. Many said the high abstention rate in Saturday’s election proved that Algerians still stood by their critiques of the system.

“Algerians don’t give a damn about this sham election ,” said former Hirak leader Hakim Addad, who was banned from political participation three years ago. “The political crisis will persist as long as the regime remains in place. The Hirak has spoken . ”

Questioning the results

Few believe the protests could lead to Tebboune’s victory being overturned. Algerian columnists and political analysts have condemned ANIE, the independent electoral authority created in 2019, and its president Mohamed Charfi for scuppering elections that the government had hoped would project its own legitimacy in the face of its critics.

Hasni Abidi, an Algeria analyst at the Geneva-based Centre for Studies and Research on the Arab World and the Mediterranean, spoke of “disorder within the regime and the elite” and said it was a blow to both the credibility of Algeria’s institutions and Mr Tebboune’s victory.

Some say his willingness to join opponents and criticize an election he won suggests infighting within the elite that is supposed to control Algeria.

“The reality is that this political system remains more fragmented and less coherent than it ever was or than people ever assumed,” said Riccardo Fabiani, North Africa director of the International Crisis Group.

The stakes

Although Mr Tebboune is likely to emerge victorious, the election will reflect the breadth of support for his policies and economy, five years after the pro-democracy movement ousted his predecessor.

Algeria is the largest country in Africa in terms of area. With nearly 45 million inhabitants, it is the second most populous country on the continent after South Africa . Presidential elections will take place in 2024, a year in which more than 50 elections will be held worldwide and will involve more than half of the world’s population.

Thanks to oil and gas revenues, the country is relatively wealthy compared to its neighbours, but much of the population has in recent years complained about rising living costs and regular shortages of basic goods, including cooking oil and, in some areas, water.

The country is a pillar of regional stability, often acting as a go-between and counterterrorism ally for Western nations when neighbouring countries — notably Libya,** Niger and Mali — are rocked by violence, coups and revolutions.

It is a major energy supplier, particularly to European countries trying to wean themselves off Russian gas, and has deep, if contentious, ties with France, the colonial power that ruled it for more than a century until 1962.

The country spends twice as much on defence as any other country in Africa and is the world’s third-largest importer of Russian arms, after India and China, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s arms transfer database.