As monkeypox vaccination programs roll out and health authorities release information about how to reduce the spread of the virus, progress on another aspect of the outbreak is lagging: its name.

On June 14, the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said the agency was:

working with partners and experts from around the world on changing the name of monkeypox virus, its clades and the disease it causes.

This followed a letter signed by 29 scientists around the world calling for a non-discriminatory and non-stigmatising name for the virus.

More than eight weeks later, nothing has changed yet.

Since mid-May 2022, as of August 10, 31,425 cases of monkeypox have been reported in 82 countries – including 66 in Australia – which historically haven’t reported cases of the virus.

During the same period, 375 cases have been reported in seven countries that have historically reported monkeypox.

While the focus has been on changing the name of monkeypox, it’s the names of the two main clades (organisms derived from a common ancestor) that are most geographically discriminatory. They are currently named the Congo Basin (or Central Africa) clade and the West Africa clade.

How is the name of a disease created?

In 2015, the WHO, in consultation and collaboration with the World Organization for Animal Health and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, identified best practices for the naming of new human diseases. These conclude:

- if the causative pathogen is known, it should be used as part of the disease name with additional descriptors; for example, novel coronavirus respiratory syndrome

- names should be short (minimum number of characters) and easy to pronounce; for example, H7N9

- potential acronyms should be evaluated to ensure they also comply with these best practices

- geographic locations, such as cities, countries, regions, and continents should be avoided; poor earlier examples include Murray Valley encephalitis and Spanish flu

- people’s names (such as Chagas disease) and the names of species (such as swine flu and bird flu) should be avoided.

Naming of the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, did not include the name of the pathogen. But it did comply with the other criteria and, fortunately, was not called Wuhan disease or China virus.

How is the name of a virus created?

The WHO is not directly responsible for naming or renaming viruses, clades of viruses and the diseases those viruses cause. Naming virus species is the responsibility of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.

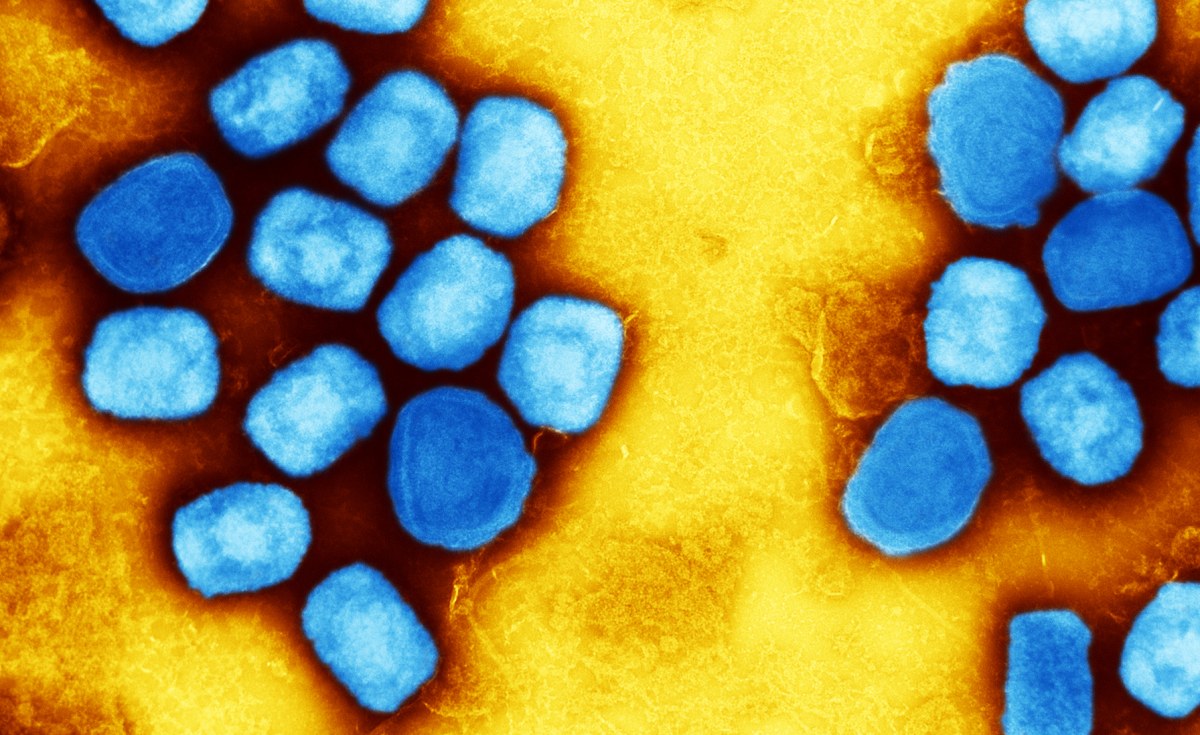

Monkeypox is a member of the orthopoxvirus family and related to smallpox, which was eradicated in 1979. Unlike other bugs, such as parasites like malaria (Plasmodium falciparum) and bacteria like “golden staph” (Staphylococcus aureus), there is still not a consistent system of assigning binomial (two words) Latinised names to viruses.

A subcommittee of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses is in the process of finalising a proposal for new binomial names for all the poxviruses, including monkeypox.

Most viral conditions have different names for the disease it causes and the virus itself.

In the case of the novel coronavirus causing the current pandemic, the short name of the disease is COVID-19, while the virus is named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Why is it so hard to change the name of monkeypox virus?

Monkeypox is not a new virus; it was discovered in 1958.

While on the face of it, the name monkeypox does not seem stigmatising (other than to monkeys) some have pointed out that monkeys are rarely associated with the Western world, and this association with the global South could be seen as problematic. The word monkey has also been employed in racist slurs against people of colour.

Monkeypox is also a misnomer because monkeys are not its natural host, which is probably in rodents. The name of the virus was given because it was first identified in laboratory monkeys in Copenhagen.

However, there is a problem with the names of the virus’s clades. The two main clades are named after West Africa and the Congo Basin, the latter causing more severe illness. This contravenes the WHO’s efforts to avoid naming viral diseases after countries or continents.

Unfortunately, many media outlets use photos of Africans, often children, with the tell-tale rash. This heightens perceptions that this is an “African disease” that has escaped to the Western world.

Despite the WHO naming criteria announced in 2015, the agency has been unable to change the name of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), caused by a camel coronavirus. In fact, one of the largest outbreaks of MERS was in South Korea.

One of the main reasons given for not changing the name is that it could disconnect future researchers from research papers written over more than five decades. This seems a weak argument because it’s almost certain that future researchers will be aware of the original name.

Another challenge is that the name would need to be changed in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) which is used around the world for medical billing and clinical epidemiology studies.

There is an apparent consensus among virologists that the new name will be something like Orthopoxvirus monkeypox. “That’s certainly the majority proposal at this stage,” according to the chair of the poxvirus subcommittee of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.

This is not much of a change and is inconsistent with WHO’s naming criteria.

There is, however, more optimism the two clades could shed their geographic names to something like clades 1 and 2.

Focus on prevention and control

During the long process of changing its name, the prevention and control of monkeypox remain the same:

- surveillance

- finding cases, isolation and contact tracing

- behaviour change communication to reduce the number of sexual partners

- vaccination of close contacts and treatment of severe illness with antiviral drugs.

This needs close engagement with communities most affected by the virus – men who have sex with men. It’s crucial to prevent stigma and discrimination, not because of the name of the virus itself but those who are most vulnerable to infection.

Michael Toole, Associate Principal Research Fellow, Burnet Institute

Source link