As the sun sets on another Black History Month, an anniversary of global significance was quietly commemorated in the United States that deserves so much more international recognition. In 2023, hip hop, arguably the greatest US contribution to global contemporary culture, celebrates 50 years of making us put our hands in the air like we just don’t care.

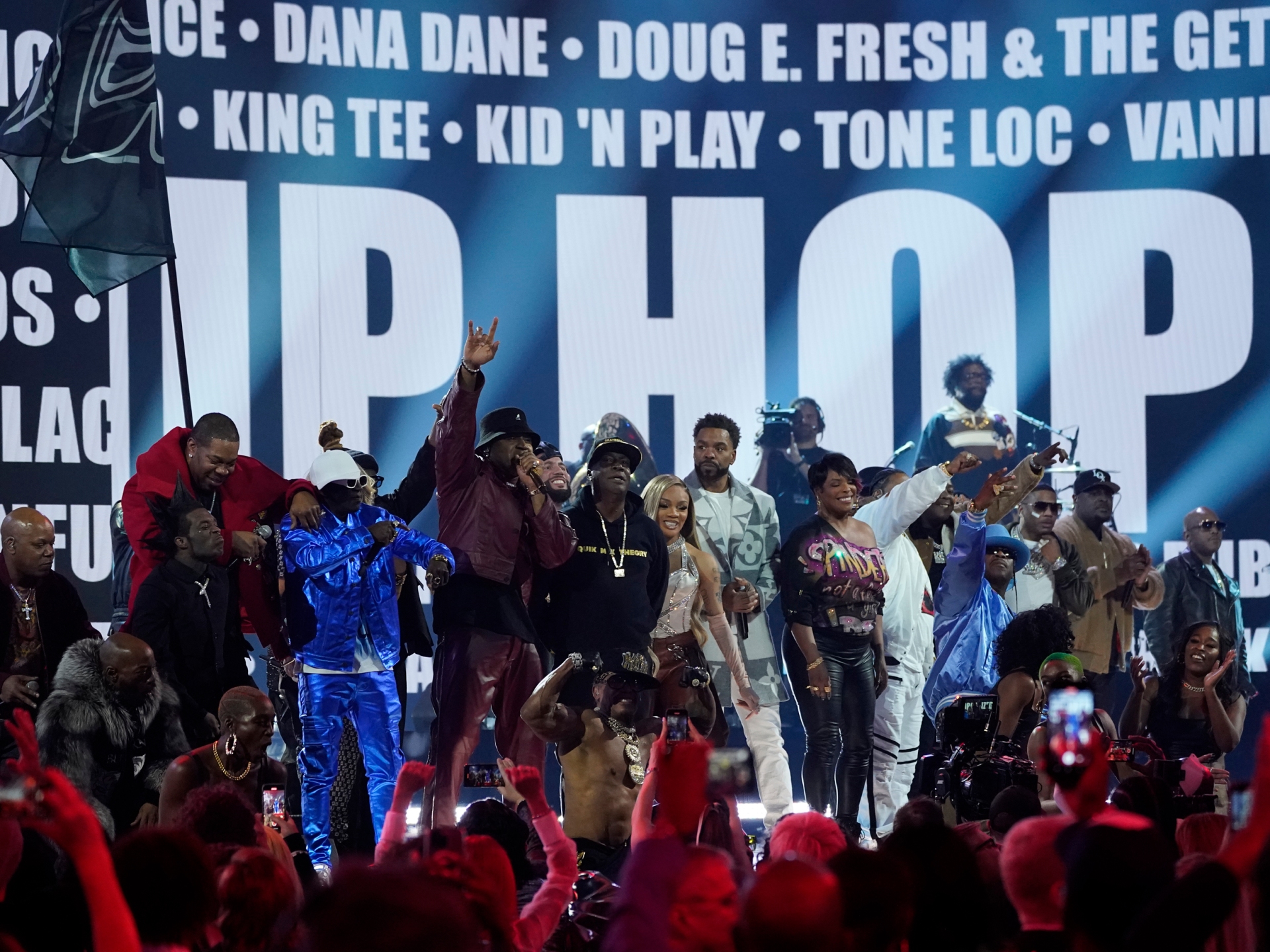

The official celebration was fitting for the US: It was marked at the Grammy Awards ceremony with performances by some of the greatest MCs to have contributed to the genre. They appeared in a single performance curated by Questlove, a member of the hip hop collective The Roots.

For lovers of the genre, it was an electrifying full-circle moment, given that 34 years ago, Will Smith, aka the Fresh Prince, and DJ Jazzy Jeff won the first ever Grammy for rap but boycotted the awards ceremony after learning that their category would not be televised. At that time, music tastemakers still saw the genre as too provocative and incomprehensible.

Even so, this year’s Grammys celebration did not go far enough in acknowledging the tremendous cultural impact hip hop has had on the world.

From the streets of New York in the 1970s to the streets of Iran in the 2020s, hip hop has become an unlikely unifier of global, rebellious youth culture. In the US, hip hop was born from the disenfranchisement and violent systemic exclusion of young Black people in inner cities.

By the time it appeared, Black culture had already invigorated US culture with jazz and rhythm and blues, among other music styles. In the 1950s and 1960s, Detroit, or “Motor City”, the cultural hub of Black music, gave Black America through Motown Records a soundtrack of love and resilience in the face of tremendous hardship, definitively proving that Black music was not only unique and exciting; it could also be tremendously profitable.

But hip hop wanted nothing to do with the genteel propriety and elaborate choreography of the Motown years. Above all else, hip hop was about anger and freedom. Hip hop was about one person and their microphone – perhaps with a deejay along for the ride – breaking all the rules and taking on the world in the process.

It makes sense, therefore, that today, hip hop is the soundtrack of rebellion and protest all over the world. In Kenya in 2007, the lyrics of Gidi Gidi and Maji Maji’s Unbwogable, an anthem about showing no fear, was the soundtrack of the failed political revolution. In 2010, Tunisian rapper El General released a song called Rais Lebled, which became the anthem of the Tunisian uprising and the Arab Spring.

Senegal’s 2011 Y’en a Marre protests, which prevented Abdoulaye Wade’s unconstitutional third term as president, were rooted in the hip hop of musical collective Keur Gui. In Chile, rap was a major part of anti-government protests in 2019 with songs like Jonas Sanche’s Dictadores Fuera (Dictators Out), decrying the alarming retreat in human rights. In Sudan, Aymen Mao’s reggae-infused hip hop became the soundtrack of the 2019 revolution.

In South Sudan, Emmanuel Jal’s hip hop is a central part of the younger generation’s demand for peace in the face of their elders’ intransigence. In Gaza, MC Gaza doesn’t just decry the Israeli blockade and occupation but also fights back against local censorship.

For young people around the world angry at systemic violence and exclusion, hip hop offers a beat to march to and an outlet for political expression.

Hip hop is to music what football – the real one, played with the feet – is to sport. Their global appeal is rooted in their simplicity: They both require very little initial capital from the participant.

As traditional instruments have fallen into disuse in many parts of the world and as instruments like guitars and pianos – not to mention the musical education required to play them – remain out of reach for most people, hip hop emerges as an elegant and accessible solution for the musically inclined.

It is global, allowing people to find inspiration using nothing else than an internet connection. It is also a particularly malleable genre of music because it doesn’t require any special insider training or knowledge; this appeals to poor and working-class people – and the global majority. The only thing truly required of putative MCs is a singular belief in their ability to be better than everyone else who steps up, and a commitment to make it so.

This is not to suggest that hip hop imposes itself onto blank cultural canvases. Quite the opposite: It underscores why hip hop more than any other genre of music has such a great claim to be the first truly global genre of music.

Consider that if the match is the basic unit of football, then rap battles are the basic unit of hip hop, allowing MCs to show off and sharpen their skills against each other. There are many global traditions of poetry that echo the dynamics of the hip hop battle.

In Sudan, poetry known as hakamat is an age-old tradition involving women taking on men or each other through poetry. Somali people are known as the nation of poets because of a long, rich history of complex oral poetry, and when not narrating odes to camels – the lifeline of desert life – it routinely descends into warm-hearted ribbing.

In Kenya, we have mchongoano, which like the former two examples is reminiscent of The Dozens, an identical US game of interactive insult that has roots in the cultural tenacity of enslaved people facing systemic violent erasure.

These global connections reaffirm many cultural links that link Black culture in the US to Africa and beyond, making the genre more culturally portable.

Inevitably, subgenres of hip hop have emerged around the world as young people layer hip hop’s raw material over their own cultures and their own circumstances, and they often encounter the same resistance that US hip hop faced in its early years.

Rap remains by far the most popular genre in terms of sales in France, which is the second largest rap market in the world after the US. But because it is the music of the banlieues, it faces stiff resistance from the authorities with even the official French music industry body SNEP calling it “overexposed” and inviting people to spend more money on other genres to diminish its impact.

In the United Kingdom, grime and drill have produced their own megastars like Stormzy and Skepta despite the UK government initially investing a great deal of resources in criminalising and policing it.

The same anti-establishment street cred that makes young people the world over fall in love with the genre inspires a backlash from the authorities in those communities. And this backlash does not stop at intimidation.

Rap continues to push back against exceptionally harsh treatment before the law in the US, where rap lyrics are still routinely used as evidence in criminal trials.

Elsewhere, hip hop musicians have been arrested, tortured and even executed for inspiring revolt. In Iran, the soundtrack for the latest wave of anti-government protests featured the rap lyrics of Toomaj Salehi, including his song Fal (Omen). He was arrested in October and his family alleges that he has been tortured.

Similarly, in Myanmar, the military junta made an example of hip hop artist Phyo Zeyar Thaw, one of four democracy activists executed in July after being accused of “conspiring to commit terror acts” in the wake of anti-junta protests.

In the US, hip hop is first and foremost Black music. As it continues to eke out a place within that nation’s musical mainstream, it stands as a reminder of how much Black America has had to fight to have a voice even while doing more to enhance the country’s global standing than just about anyone else.

Yet in 2023, US hip hop has undoubtedly lost its political edge, swapping defiant (if routinely misogynistic) lyrics for celebrations of sex and wealth. Jay Z, by many accounts the best English-language rapper alive, is far less likely to give us a primer on the US Constitution’s Fourth Amendment protections against involuntary search and seizure as he did in 2004’s 99 Problems and more likely to remind us that he is an impossibly wealthy man who can today buy his way out of whatever power throws at him. That is, of course, his well-earned prerogative.

But for the rest of the world, hip hop remains a talisman of youth creativity and revolt – a critical element in the soundtrack for generational resistance. And for that, hip hop deserves a resounding happy birthday from the rest of the world as well.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.