Hired as a so-called tax collector by several influential families, Captain Nwokuha has a fearsome look as he walks around with a piece of wood to enforce his authority at a busy and chaotic road junction in the southern Nigerian city of Port Harcourt.

The 34-year-old’s job is to collect “taxes” for what he calls the “community” from taxis and 18-seater buses that operate in that part of the city.

Mr Nwokuha’s work has its roots in an old tradition, when businesses used to pay a one-off fee, or gift a drink, as homage to their hosts for good tidings.

But now it has turned into what critics say is an extortion racket.

Some families, claiming to act on behalf of local communities, demand fees from businesses, be they taxi drivers or market traders, operating in what they see as their domain.

Mr Nwokuha says he collects 5-7,000 naira (£5-7; $6.50-9) a day – a reasonable amount in Nigeria.

Married with two children, he keeps some of the money while the rest is given to five powerful families in the community – where it gets lost in a trail of private pockets.

So-called tax collectors or third-party agents are also used by Nigeria’s states and local governments to collect some taxes.

“These agents use private accounts and make deductions before remitting to the government,” says Michael Ango, a former government tax official who is now with private firm Andersen Tax.

“[Their methods] create the impression that the state is using might and muscle rather than legitimacy.”

Led by new President Bola Tinubu, Nigeria’s federal government has vowed to crack down on what it calls “touts, miscreants and self-imposed tax collectors”.

As for Mr Nwokuha, he believes he is playing a positive role, doubling up as a traffic officer who resolves disputes in the cut-throat taxi business.

“If there is a fight among the drivers I settle it,” says Mr Nwokuha, who patrols Port Harcourt’s lucrative Rumuola interchange on weekdays from dawn to dusk in his fluorescent vest.

Before a driver sets off, the man with “task force” written on his vest receives 20% of the passengers’ fares.

“The taxis are not allowed to operate here,” says Mr Nwokuha, pointing at a “no parking” sign painted in police colours.

“But if they choose to, then they have to pay to the community,” he tells the BBC.

On the rare occasion that a driver refuses to pay, they could have a side mirror or taillight broken – or their registration plates removed.

If they dare fight back, they might feel Mr Nwokuha’s wooden stick cracking their skull.

Mr Nwokuha is doing what ought to be the job of employees of the local council. Nigeria has 780 local councils but most of them are hardly functional.

The vacuum is filled by men like Mr Nwokuha – or just about anyone who can set up a roadblock and enforce their authority.

These tend to consist of a wooden bar between two rusty barrels, and home-made spikes for drivers who want to be smart by trying to avoid them.

They are most common in the richer southern parts of Nigeria, including highways where tax collection is done on behalf of some state governments.

One lorry driver tells the BBC he pays as much as 80,000 naira (£80; $100) as he travels through scores of roadblocks on his way from Nigeria’s biggest city, Lagos, to Imo in the east: a distance of 540km (335 miles).

“Between Edo and Port Harcourt [alone, a journey of about 280km] there are 15 such roadblocks,” he adds.

Expressing a similar view, a cold-chain logistics operator says: “There are numerous haulage taxes, there is one called revenue, there is a radio tax, there is a tax for loading, another for parking, one for unloading.”

And that is not including the bribes he often has to pay police officers as he drives around the country.

Clement Akanibo, of Nigeria’s Chartered Institute of Taxation, describes it as “akin to collecting tax at gunpoint”.

“It makes it difficult to do business and increases the final cost by as much as 15%,” he says.

It is unclear how Mr Tinubu plans to end this, but he will need the support of state and local governments as these taxes fall under their jurisdiction – not that of the federal government.

At its heart lies a powerful system of patronage that sees a portion of the money going into the pockets of politicians, powerful families, and the army of unemployed men like Mr Nwokuha.

Mr Tinubu’s government says it wants to overhaul the entire tax system to boost its revenue so it can increase the amount it spends on services like health and education, as well as pay off its ballooning debts.

It has set itself the target of increasing the tax-to-GDP ratio to 18% within the next three years.

Official Nigerian data shows the ratio was around 11% in 2021, lower than what the World Bank reported for Kenya (13%) and South Africa (26%).

For now, Mr Tinubu’s government is focusing on the taxes it is responsible for – including Value-Added Tax (VAT).

The federal government does not use so-called tax collectors, expecting businesses to make direct payments.

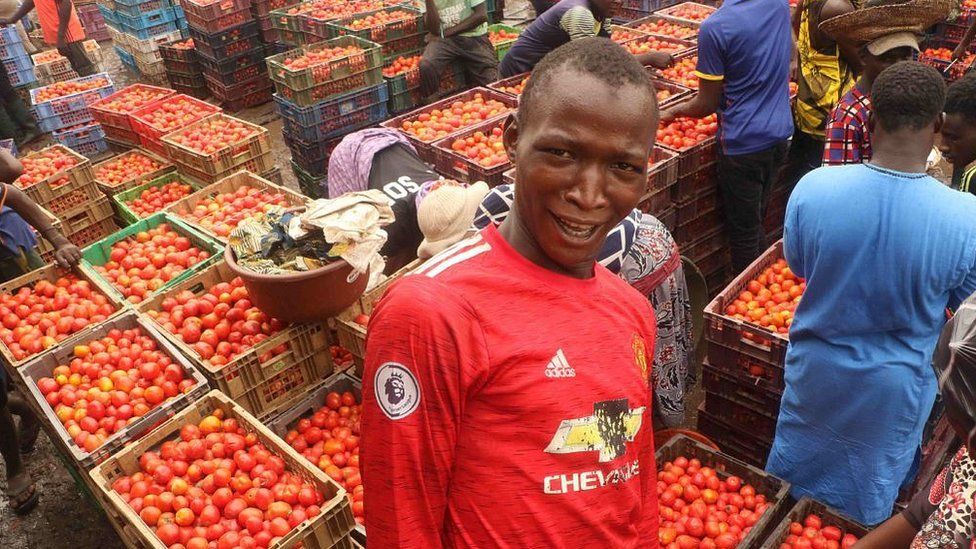

In what appears to be an attempt to end tax evasion, it wants to digitise VAT payments, starting with the 40 million-strong association of market traders.

This won’t be easy as most of them do not keep financial records and have never paid VAT, so might resist the move amid the current economic hardship.

But if the plan works, Mr Tinubu’s government could then hope to persuade state and local governments to drop their archaic system – something that many Nigerians would welcome as it would free them from the clutches of menacing tax collectors like Mr Nwokuha.