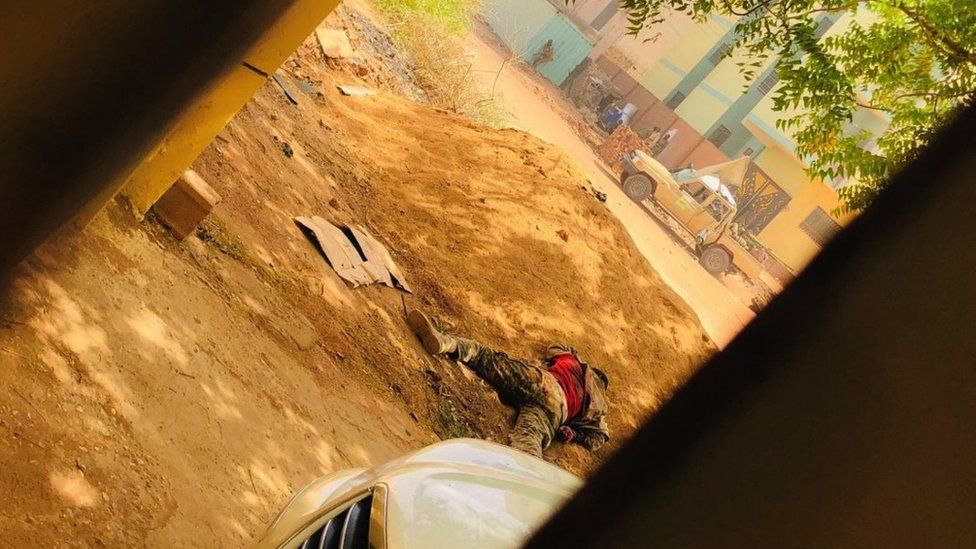

After seven weeks of a bitter battle for control of Sudan’s capital, some Khartoum residents are grappling with a problem they never envisaged – what do with all the dead bodies which are piling up on the city’s streets.

Warning: This story contains graphic photographs and description throughout.

“I have buried three people inside their own houses, and the rest just by the entrance of the road that I live on,” said Omar, whose name we have changed.

“That’s better than opening the door and seeing a dog chewing on part of a dead body.”

No-one knows how many people have died so far but it is believed to be well over 1,000, including many civilians caught in the crossfire.

With two military factions – the regular army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group – battling it out despite various ceasefires, it is far too dangerous to try and go to a cemetery.

Omar has buried at least 20 people.

“A neighbour of mine was killed in his house. I couldn’t do anything but remove the ceramic tiles in his house, dig a grave and bury him,” he told the BBC.

“Corpses are left to decay in the heat. What can I say? Some neighbourhoods in Khartoum are now turning into cemeteries.”

Last month, Omar dug graves for four people by a road just a few metres away from his house in the al-Imtidad district of Khartoum. He said he knew of other people who had to do the same in nearby neighbourhoods.

“Many of those who were killed were buried in areas near Khartoum University, close to Seddon fuel station, a well-known landmark. Other corpses were buried in neighbourhoods close to Mohamed Naguib road.”

There are no official figures for the number of people buried in houses or neighbourhoods in Sudan, but Omar said “it could be dozens”.

Hamid, whose name we have also changed, has a similar experience.

He told the BBC he had buried three army personnel in a communal area of Shambat city, 12km (7.5 miles) outside the capital, after a military jet crashed.

“I was in the area by chance. A group of five people and myself moved the corpses away from the debris, and buried them in an area surrounded by residential buildings.”

Hamid, a property agent who has lived in the area for 20 years, believed that this was a “work of mercy”.

“It is not important where we bury the dead,” he said.

“Burying them is the priority. It is a charitable thing to do. The journey to the graves [in cemeteries] could take days and snipers are everywhere.

“We are trying to help society avoid a health disaster. It is a religious and moral duty.”

‘Burying the truth’

Despite the good intentions, these actions could unwittingly destroy evidence of war crimes, the head of the doctors’ union, Dr Attia Abdullah Attia, said.

He warned that these “amateurish” methods of burial could “bury the truth”, adding that clues of how people died could be destroyed.

Dr Attia said bodies should be identified and buried in graves in a timely and dignified manner.

He insisted people should leave the burial process to the health authorities, the Red Cross and the Sudanese Red Crescent.

“Burying the dead this way is not justified. The burial process should have the presence of official governmental representatives, the prosecution, forensic specialists and the Red Cross. It is also important to take DNA samples.”

When asked why he believed it would be possible to follow these practices in a country where the health system and law and order have collapsed, he said foreign countries should play a role.

The two volunteers, Omar and Hamid, both said they take photographs of the faces and bodies of the dead before they bury them, which can help identification in the future.

But Dr Attia also warned that unsafe burials could lead to the spread of disease.

“Burying the dead at a shallow level makes the graves more likely to be exhumed by stray dogs. The correct way of burying isn’t applied here, because a solid object or bricks need to be placed in the grave to prevent the bodies being exposed,” he told the BBC.

Hamid, however, says most Sudanese people were aware of the proper way to dig a grave where the bodies are placed “at least one metre under the ground”.

Some organised efforts to bury bodies are under way.

A man, who we are calling Ahmed, volunteers with the Red Cross to clear bodies from the streets.

“I take photos of the face and body, record if it is a new dead body or has decayed [and] give it a number.”

He said they keep a file for every body for future identification.

Despite Dr Attia’s criticism, people feel they have no choice due to the collapse of the public health infrastructure.

On 11 May, videos circulated on social media showing the burial of two Sudanese female doctors, Magdolin and Magda Youssef Ghali, in their garden.

Their brother, who we are not naming, told the BBC in a video call that burying his two sisters in the house was “the only solution”.

“They were left for almost 12 days without burial,” said the brother in tears.

“The neighbours reported a foul smell coming from the house so people volunteered to bury them in one grave in the garden.”

The health authorities have been working with the Red Cross and the Sudanese Red Crescent to move bodies to cemeteries. But fighting has hindered the arrival of the burial teams.

As people try to survive and bury their dead in a dignified manner, the thought of a war crimes tribunal feels like a remote possibility in the midst of so much violence and loss.

The story of the siblings captures the horror that people are facing every day.

“My sisters were buried in one hole in their garden. I would never have imagined that would be their end,” said their brother.