CNN

—

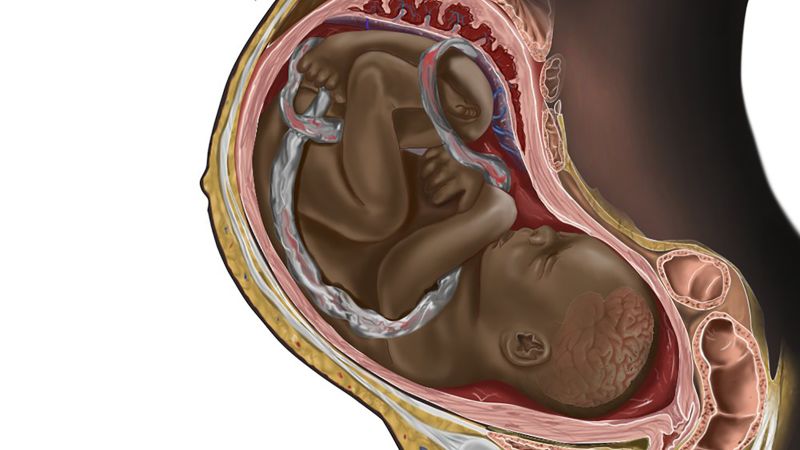

At first glance, the image looks like a standard drawing that could easily be found in the pages of a medical textbook or on the walls of a doctor’s office.

But what sets apart the illustration of a fetus in the womb that recently captured the attention of the internet is a simple, yet crucial, detail: its darker skin tone.

The image, created by Nigerian medical student and illustrator Chidiebere Ibe, struck a chord with countless people on social media, many of whom said that they had never seen a Black fetus or a Black pregnant woman depicted before. It also brought attention to a larger issue at hand: A lack of diversity in medical illustrations.

(While most fetuses are red in color – newborns come out dark pink or red and only gradually develop the skin tone they will have for life – the medical illustration is intended to represent patients who aren’t used to seeing their skin tones in such images.)

Ibe said in an interview with HuffPost UK that he didn’t expect to receive such an overwhelming response – his fetus illustration was one of many such images he’s created as a medical illustrator, most of which depict Black skin tones. But it underscored the importance of a mission he’s long been committed to.

“The whole purpose was to keep talking about what I’m passionate about – equity in healthcare – and also to show the beauty of Black people,” he told the publication. “We don’t only need more representation like this – we need more people willing to create representation like this.”

CNN reached out to Ibe for comment, but he did not expand on the topic further.

Ni-Ka Ford, diversity committee chair for the Association of Medical Illustrators, said that the organization was grateful for Ibe’s illustration.

“Along with the importance of representation of Black and Brown bodies in medical illustration, his illustration also serves to combat another major flaw in the medical system, that being the staggering disproportionate maternal mortality rate of Black women in this country,” she wrote in an email to CNN.

Medical illustrations have been used for thousands of years to record and communicate procedures, pathologies and other facets of medical knowledge, from the ancient Egyptians to Leonardo da Vinci. Science and art are combined to translate complex information into visuals that can communicate concepts to students, practitioners and the public. These images are used not just in textbooks and scientific journals, but also films, presentations and other mediums.

There are fewer than 2,000 trained medical illustrators in the world, according to the Association of Medical Illustrators. With only a handful of accredited medical illustration programs in North America, which tend to be expensive and admit few students, the field has historically been dominated by people who are White and male – which, in turn, means the bodies depicted have usually been so, too.

“Historically [medical illustrations] have always featured white able bodied male figures and still do in the present day,” Ford said. “Bias towards one body type in medical illustration marginalizes everyone else.”

Studies have backed up this lack of diversity. Researchers at the University of Wollogong in Australia found in a 2014 study that out of more than 6,000 images with an identifiable sex across 17 anatomy textbooks published between 2008 and 2013, just 36% of the depicted bodies were female. A vast majority were White. About 3% of the images analyzed showed disabled bodies, while just 2% featured elderly people.

Diversity in the field of medical illustrations (or lack thereof) matters because these images can have implications for medical trainees, practitioners and patients.

“Without equitable representation and the perpetual use of only white able bodied patients depicted in medical textbooks, medical professionals are limited in their ability to accurately diagnose and treat people who don’t fit that mold,” Ford said. “Medical professionals can then tend to rely on racial stereotypes and generalizations because of this knowledge gap on how symptoms present differently on darker skin tones, leading to poorer care.”

A study by the same University of Wollogong researchers published in 2018 found that gender-biased images from anatomy textbooks increased medical students’ scores on implicit bias tests. Another study published in the journal Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery – Global Open in 2019 found that White patients were overrepresented in the images of plastic surgery journals, which the authors suggested could potentially influence the care non-White patients received.

“For decades, peer-reviewed academic publications have used photographs and images that inadequately portray the diversity in demographics of patients affected by particular diseases,” the researchers wrote. “This is particularly striking in the lack of diversity in medical illustration. These inequities in medical reporting can have lasting downstream effects on the accessibility and provision of healthcare.”

Ford said that those who aren’t often depicted in medical illustrations “can feel left out and unacknowledged in a healthcare setting, leading to feelings of distrust and isolation when receiving care.” She also said that medical professionals might feel less empathy for groups who aren’t represented – people who are Black, brown, women, transgender or nonbinary – which can lessen the quality of care they receive.

Inequities in health care have been well-documented, with studies showing that Black patients are more likely to experience bias and be misdiagnosed for certain conditions. Research has also shown that a substantial share of White medical students and residents hold false notions about biological differences between Black and White people, which can lead to racial bias in the ways their pain is perceived and treated.

Despite the persistent need for medical illustrations to depict the full scope of human diversity, the field is beginning to see changes, medical illustrator Hillary Wilson told CNN.

Wilson, whose illustrations depict Black people in infographics about eczema, sun damage, alopecia and other conditions, said both patients and practitioners could benefit from seeing diversity represented in medical illustrations. And through her work, she’s attempting to humanize people of color and other marginalized groups by doing just that.

“The reality is that there are so many different types of people that exist,” she said. “To me, a resource isn’t complete if I didn’t at least consider that and try my best to account for the fact that there are so many different types of people.”

While Ibe’s image of the Black fetus seemed to mark a departure from the norm, Wilson said she hopes that in the future, seeing Black skin tones in medical illustrations will become routine.

“Eventually, I hope it can just become one of the things that’s expected,” she added.